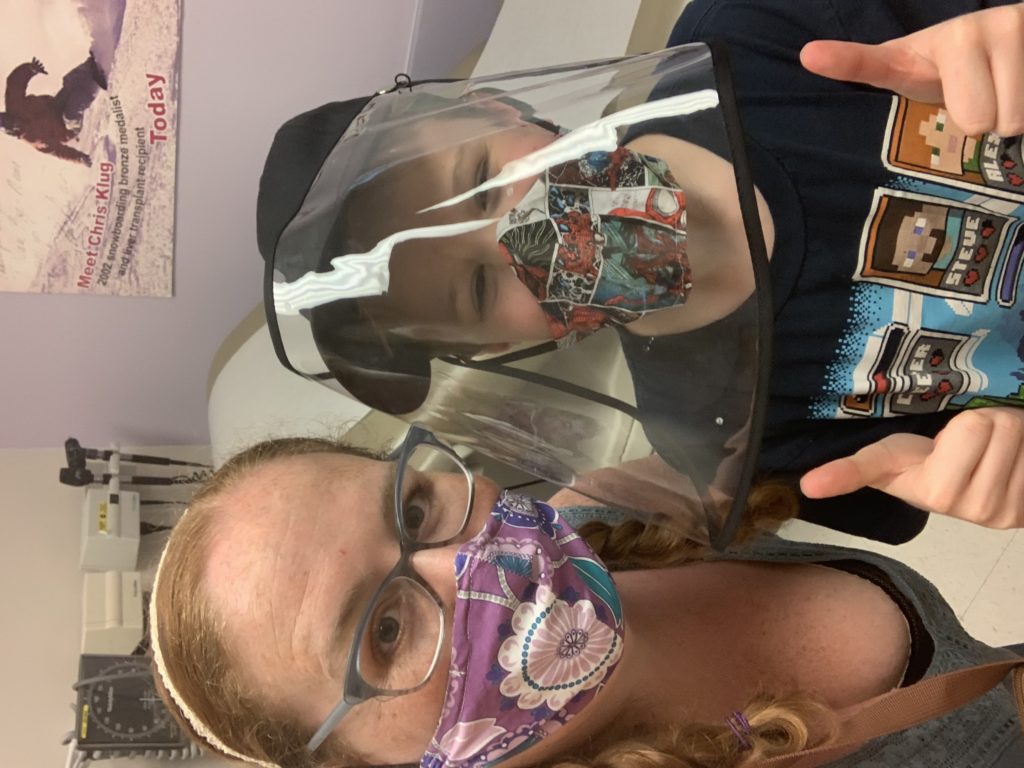

WASHINGTON — For Tasha Nelson, exercising her right to vote has become a life-and-death situation. As a 39-year-old mother of five with Behcet’s disease and a son with cystic fibrosis, Nelson and her family are at a high risk for the novel coronavirus.

“With my particular disabilities, for the first time, I’m terrified to go vote,” said Nelson, who was diagnosed in 2016 with Behcet’s, an extremely rare and incurable autoimmune disease that affects both the large and small vessels of the vascular system. Her 8-year-old son lives with cystic fibrosis, a rare and potentially fatal disease that affects all of his major organs, including his lungs.

Like many others, Nelson has self-isolated since March 6 and is following all guidelines to keep her family safe. She disinfects groceries before bringing them into her home and avoids taking any chances that could compromise her and her son’s health.

Yet, as the nation celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act last week, activists like Nelson warn that the current voting system is still hostile to the 61 million people living with disabilities in the United States — a concern that has been intensified by the additional hindrances caused by the pandemic.

To Nelson, exercising her right to vote is important because elected officials will vote on laws that directly affect her family’s life, including access to health care, education and community services. “Voting is the most basic and fundamental right of citizens of this country,” Nelson said. “And the pandemic adds an extra level to my vote.”

As a resident of Virginia, a state that recently allowed no-excuse absentee voting and limited early voting, Nelson was able to go online and register to vote absentee with little difficulty, which she refers to as “a step in the right direction” because people with disabilities no longer have to go to crowded polling places or prove they need to receive an absentee ballot.

But eight states — Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Kentucky, Indiana, New York and Connecticut — still require voters to provide an excuse beyond fear of the coronavirus to receive an absentee ballot. For the 52 million voters in these states, in-person voting remains the only option unless they are approved to vote absentee for reasons such as military deployment or illness.

Several states also require voters to find a witness or notary to sign their ballot in order for their vote to be counted, an additional burden that could present an obstacle to voters with disabilities during the pandemic.

“Forcing people, especially the high risk population, to leave their homes during shutdowns — your country is asking you to risk your life to tell them what you as a constituent need,” Nelson said.

Other challenges

Imani Barbarin, a disability advocate and director of communications and outreach for Disability Rights Pennsylvania, says there are many additional hindrances disabled citizens face when it comes to voting despite protections from the ADA. As the host of “Votes for Access,” a five-part video series that includes interviews with disabled citizens about their experiences voting, Barbarin, who has cerebral palsy, says “we still have a lot of work to do in terms of disability and inclusion at the ballot.”

One disabled voter told her about his experience fighting for his right to vote for 20 years, routinely filming his experiences with inaccessibility at polling places. In one video, he showed viewers that the Accessible Voting Unit he needed to use wasn’t even plugged in.

Barbarin added that voters have expressed frustration over a lack of plain language ballots and the obstacles blind and low-vision people encounter when receiving ballots by mail. In fact, several lawsuits have been filed this month in states across the country alleging that mail voting systems are inaccessible to visually impaired voters.

Last Monday, five Virginia residents and members of the state affiliates of the National Federation of the Blind and the American Council of the Blind filed a joint lawsuit in federal court claiming they are unable to independently mark a paper ballot due to their disabilities, which violates the ADA.

“The Absentee Voting Program provides no alternatives to accommodate individuals with print disabilities to enable them to vote privately and independently,” the lawsuit claims. “As a result, individuals with print disabilities must choose between their health and their right to vote because they are forced to go to their local electoral board or polling place to privately and independently mark their ballots.

Another challenge that Barbarin says affects voter turnout within the disability community — as well as among Black and Brown voters — is a lack of accessible public transportation for people with disabilities who live in rural areas or several miles from a polling place.

Nelson added that some voting sites across the country are still inaccessible to voters with mobility disabilities, from issues like not having curb-cuts for wheelchairs to requiring voters to walk up stairs to enter.

“It’s absolutely a way to turn away the disability vote when you are making voting inaccessible,” Nelson said. “There’s already real voter suppression in the disability community.”

Despite their advocacy for increased mail-in-voting, Nelson and Barbarin said that in-person polling places still need to be made accessible for people with disabilities during the pandemic because some voters rely on assistive technology to vote privately and independently or need assistance to cast their votes.

“Simply because somebody has access to a ballot physically does not mean that they can access it through their senses,” Barbarin said. “There are some blind and low-vision voters who cannot access a mail-in-ballot privately and independently.”

Advocating for reform to increase voting accessibility

With over 65,000 Twitter followers, Barbarin’s advocacy on social media has been bringing more attention to disability rights to a younger generation as she fights for reforms to make voting more accessible, such as calling for universal no-excuse absentee voting and a standardized mail-in ballot election system.

“Mail-in ballots have made voting more accessible to people with certain types of disabilities,” Barbarin said. “But we can’t always confuse proximity with accessibility.”

Across the nation, activists and advocacy groups have been working to create a more accessible voting process that would provide disabled citizens with more accommodations before the November election. In Wisconsin, a swing state where 23,000 absentee ballots were thrown out during the April primary largely because voters or witnesses missed a line on the form, a disability voting coalition recently released a set of policy recommendations aimed at enfranchising voters with disabilities.

“Because of concerns related to COVID-19, many voters with disabilities were unwilling to vote in person and risk their health,” the memo from the Wisconsin Disability Voting Coalition reads. “For those who attempted to vote in person, barriers included failure to offer curbside voting, long lines for curbside vote, or long lines to enter the polling place.”

The coalition calls for lawmakers in Wisconsin to make the absentee ballot process more accessible and ADA compliant before the November election so that voters with disabilities have access to options for voting privately and independently. They also call on lawmakers to provide an exemption for witness signatures for voters who self-certify that they could not safely get a witness or notary during the pandemic.

California recently announced that it will start proactively mailing ballots to registered voters, joining universal vote-by-mail states such as Colorado. Some states will also send every registered voter an absentee-ballot application.

But in other states, voters must have access to a computer and the internet — as well as an address — in order to request and receive an absentee ballot, Nelson said. Additionally, absentee ballots must be mailed back by specific dates that vary by state in order to count. For example, in Texas, ballots cast by mail must be received by 5 p.m. on Nov. 4, the day after the election.

“If there’s any kind of stock up in the mail, if there’s storms and they are held up a day or two, and your vote is received days after the election, it won’t be counted,” Nelson said.

In Washington state, however, there are no restrictions for when ballots must be received. As long as ballots are postmarked by Election Day, they will be counted.

These disparities in the voting system based on locality can make it extremely difficult for citizens to cast their ballots. As President Trump floats the idea of delaying the election due to unsubstantiated allegations that increased mail-in-voting due to the pandemic would result in fraud, Nelson believes having a standardized voting system would make it easier to regulate and check for fraud.

“Voting should be the most streamlined, easy to access, simple thing to do nationwide,” Nelson said. “It should be done the same way everywhere.”

The fight for disability representation

As a Black woman born with cerebral palsy, Barbarin noted that not all disability experiences are universal, but she says it is important for everyone to pay attention and listen. In fact, 30-50% percent of all people killed by law enforcement officers are disabled, according to a study by the Ruderman Family Foundation, a statistic that has become more apparent amid the Black Lives Matter movement.

“We really need to start listening to intersectional voices — Black, disabled voices — who are speaking up and speaking out about these occurrences,” Barbarin said. “We need to make sure that we provide a space in the room for Black and Brown people with disabilities to speak about their experiences and power.”

As Barbarin continues the fight for disability representation, she also called for more funding for community-based services and investing in accessible neighborhoods after hearing a story about a Black woman who was arrested for protesting on the street instead of a sidewalk — even though the sidewalk was inaccessible to her.

She says the next hurdle for disability rights is the passage of the Disability Integration Act, which is currently stalled in the House and would require insurance providers and government entities to provide long-term services and support so that people with disabilities can live in integrated settings, such as their own homes where they can lead independent lives. The proposed legislation would strengthen the ADA’s community integration mandate and bolster the Supreme Court’s 1999 ruling in Olmstead v. L.C., which found that people with disabilities have the right to access services in the community.

While the activism of the disability community has already led to many big successes, including the passage of the ADA, 504 Rehabilitation Act, IDEA Act and the Olmstead decision — which each granted people with disabilities greater protection and accessibility — Barbarin says there are still places the ADA falls short, even 30 years after its enactment.

“It didn’t do a lot to change attitudes about disability,” she said. “That requires a lot of allies in support.”

In order to change attitudes about people with disabilities, Barbarin wants to see more disabled people in political office, in TV and film and as educators, as well as less stereotypes and bias towards those with disabilities.

“There’s this instinct upon our society to kind of shuffle disabled people off and away into the side, but we really need to be on the forefront of this,” she added. “It ensures that we have a more holistic view of the horrors that our communities face.

This article is part of a reporting effort by The GroundTruth Project on voting rights in America, with support from the Jesse and Betsy Fink Charitable Fund, Solutions Journalism Network and MacArthur Foundation.