The seeds of World Press Freedom Day were sown in Windhoek, Namibia in 1991.

Namibia had just won its independence from South Africa and Gwen Lister, award-winning founder of The Namibian newspaper, helped welcome journalists from around the world to her home country for the annual UNESCO conference.

Lister had been jailed and her publications banned for her political reporting. There the group adopted the Windhoek Declaration for the Development of a Free, Independent and Pluralistic Press.

That declaration has become the foundation for global press freedom efforts, and the date of its adoption, May 3, is World Press Freedom Day.

This year the UNESCO conference will return to Windhoek to focus on the theme: “Information As a Public Good.”

Today, attacks and arrests of journalists continue unabated in many countries, including here in the United States. According to Reporters without Borders’ most recent Press Freedom Index, the United States ranked number 44 in the world out of 180 countries in its respect for and promotion of press freedom. Namibia ranked number 24.

As The GroundTruth Project launches its Report for the World initiative in Nigeria (ranked no. 120) and India (ranked no. 142) with emerging journalists covering under-covered issues pertinent to their local communities, Lister spoke to The GroundTruth Project about how the conversation around press freedom has evolved over the past 30 years, new threats to press freedom, and her advice to young journalists today.

* * *

“Now the disinterest in good journalism is palpable on our continent, with Afrobarometer surveys showing that Africans care far less about rights like press freedom than they did only a few years back.” – Gwen Lister

GroundTruth: World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) returns to its African roots this year, where WPFD kicked off at the UNESCO conference in Windhoek in 1991. What are the most striking differences (or are there any) in the discussions of press freedom in 1991 compared to today?

Gwen Lister: “The most striking difference between the time when we adopted the Windhoek Declaration in 1991 – an era dominated by print, radio and TV, to a lesser extent – compared to three decades later, is what I would term the social media tsunami. Then our concern, as mainly print journos who attended the Windhoek Seminar, was mainly about making a stand for newspapers which could be ‘free, independent and pluralistic,’ and to break with the domination of government control, from apartheid South Africa in the south to one-party states further afield. Some brave journos, sometimes dubbed the ‘guerrilla typewriters,’ had defiantly set up independent newspapers in the ‘80s in the face of strong government opposition, and those who did so were often jailed, harassed and worse, for daring to do so. From the much-imprisoned Pius Njawe of Le Messager in Cameroon to Fred M’Membe at the Weekly Post in Zambia, Onesimo Makani-Kabweza in Zimbabwe, Kenneth Best of Liberia and others, many of these independent journalists gathered in Windhoek in 1991 for the first time to share their stories of hardships under draconian governments and their hopes for a bright future for independent media as essential to the economic development and democratic well being of any country.

“Three decades later, and print is imperiled in terms of sustainability but also in terms of loss of public trust, a situation made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic which has swept the globe. Now the power lies in the hands of the tech giants and traditional advertisers and people in general are flocking to social media, creating further dilemmas for those who want print to survive.

“The world’s media are facing far different problems to those they faced three decades ago, where propaganda, rather than disinformation, was the enemy, but the people were largely on their side. Now the disinterest in good journalism is palpable on our continent, with Afrobarometer surveys showing that Africans care far less about rights like press freedom than they did only a few years back.”

What does “information as a public good” mean to you?

GL: “’Information as a public good’ is to me the antithesis of disinformation. Journalists need to introspect very deeply at WPFD 2021 about the future of good journalism and how to save it. We also need to think long and hard about how to innovate in terms of the sustainability challenge, how to bring back the public trust and assist with media literacy, while helping them to resist clickbait and guide their attention back to news and information they can trust, and which in turn will promote more informed citizens who are thereby enabled to be active participants in their own development and their democracies, where such exist.”

What are the key press freedom issues in Africa today?

GL: “Impunity for crimes against journalists is always top of the list. How to create environments in which it is safer for journalists to do their work, and to urge governments to provide enabling conditions to this end. Press freedom in Africa is often on a one step forward, two steps back trajectory, and many of the continent’s democracies are fragile at best. New threats come in the form of laws in the guise of cybersecurity which are used to silence freedom of expression, particularly when it comes to political oppositions. Where once newspapers were burned and bombed, now authorities have resorted to shutting down the internet for spurious reasons, but mainly to muzzle political dissenters. These are just a few examples of current threats to press freedom.”

Your life as a press freedom advocate has been extraordinary. What work are you most proud of, and what would you do differently if you could?

GL: “While it was hard to keep the newspaper alive at a time pre-independence when the South African colonial government tried every means at their disposal to shut us down, whether it was through arrests, harassment, intimidation, firebombing, etc., the 1990 post-Independence challenge to achieve self-sufficiency as donor funding dried up, was probably our biggest challenge. But we managed to do that, setting the newspaper up as a non-profit trust; only to have it face other threats to its sustainability several decades after its founding in 1985.”

What advice do you have for today’s generation of journalists or anyone contemplating getting into the business?

GL: “My usual answer to this question to all young people contemplating a future – to follow their passion. And if journalism is that dream, then it’s important for them to realize journalism is about public service, a 24/7 calling; that it requires a multitude of skills and characteristics such as curiosity; a never-ending quest for the truth, bravery, professionalism, ethical behavior… the list is long, and that they shouldn’t embark on a career in journalism unless they have the attributes to do so, or they risk bringing the craft into (further) disrepute.”

What progress would you like to see Africa, or even the world, make in the next decade in terms of press freedom?

GL: “One of the big campaigns across this continent currently is access to information laws. A number of African countries have committed themselves to serve the peoples’ right to know, but I don’t think the political will exists currently to truly dispense with secrecy in favor of transparency – a move that would not only benefit journalism, investigative journalists in particular, but most importantly, the people themselves. So a big change of heart is necessary for governments not just to put laws into place which will either never see the light of day, or be countered by other repressive legislation, such as cybersecurity laws, but to commit themselves to the understanding that all the information they hold close to their chests should be in the public domain, and citizen access should not be restricted in this regard and people should not be kept in the dark.”

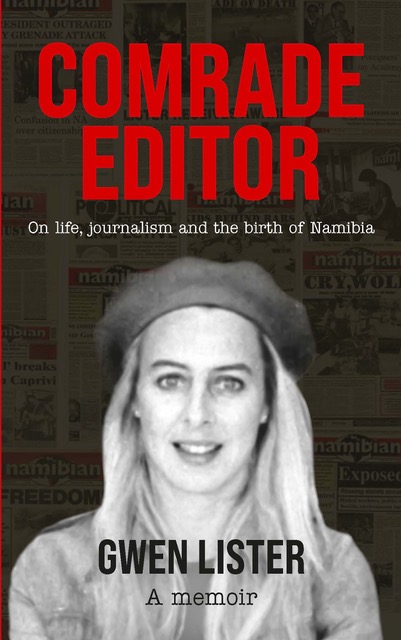

Gwen Lister is the founder of The Namibian newspaper and was named a World Press Freedom Hero in 2000 by the Vienna-based International Press Institute. She is also the recipient of the International Press Freedom Award from the Committee to Protect Journalists in 1995. Lister serves on the advisory board of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard in 1995. Lister is author of the memoir, “Comrade Editor and the Strapline: On Life, Journalism and the Birth of Namibia,” published by Tafelberg, South Africa and scheduled to be released on May 28.