Artemis Joukowsky was a high school freshman working on a class assignment in 1976, when his mother shared something profound about his grandparents, a Unitarian minister named Waitstill Sharp and his wife, Martha.

The Sharps had received a call from the American Unitarian Association in January 1939. The mission: Go to Czechoslovakia to help save Jews and other refugees from Nazis overtaking the Sudetenland.

The American public was largely unsympathetic to the refugees’ plight. But the Unitarians were allied with Czech progressives, and they felt compelled to “do something.”

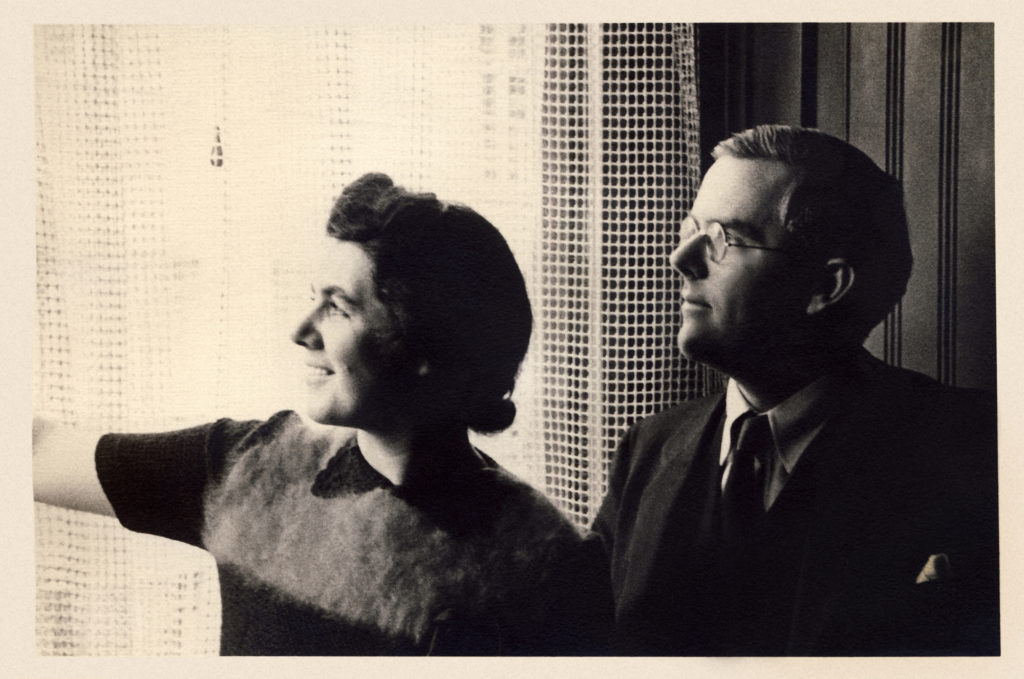

Although the Sharps had two small children and lacked experience in foreign aid, they accepted the daunting invitation, as Joukowsky and co-director Ken Burns illustrate in their new documentary, “Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War,” which premieres on PBS on Tuesday, Sept. 20.

They left their congregation at the Unitarian Society in Wellesley, Mass. to “face the evil that faces us,” as Waitstill declared in a sermon before departing. The duo worked as part of an underground resistance in London, Prague and Paris, learning to send coded messages and direct resources to refugees while evading detection. The Sharps ultimately brought dozens of persecuted men, women and children out of Europe and into safety in the United States.

While Israel’s Holocaust remembrance center, Yad Vashem, honored the Sharps as “Righteous Among the Nations” in 2006, their story remains largely unknown, even among Unitarians.

“The Unitarians don’t promote themselves because they feel like that is immodest,” said Joukowsky, a lifelong Unitarian, sitting in the recently finished Sharp Room of the Wellesley church, where portraits of his grandparents hang side by side. The smell of fresh paint lingers in this wing of the historic church, which Joukowsky helped to rebuild after it flooded in 2013.

“My grandparents never published their own memoirs,” he said. “They had these stories in their bodies and in their minds, and they never published.”

Joukowsky is now pushing their story into the spotlight with help from Burns and the actor Tom Hanks, who narrates Rev. Sharp’s character. The director, investor and activist is mindful that, as the world faces the worst refugee crisis since the time of the Nazis, the American public is veering toward a xenophobic, exclusionary mindset that would have been right at home in the 1930s.

“History is never the past. We are always living in the present,” Joukowsky said. “The fact that the refugee crisis today is so similar and Islamophobia is so intense – that fear of ‘the other.’ It does really bring you back to Father [Charles] Coughlin and this era of isolationism. It’s a natural tendency in American history.”

As he informs the public about the role Unitarians like the Sharps played in fighting authoritarianism and embracing the displaced, Joukowsky hopes to mobilize a new generation of religious progressives to work against that tendency.

“The film is trying to make a statement about the desperate need to bring refugees to safety, wherever that might be. The Sharps stood for a tolerant, interfaith world. We have to explain that this comes from their faith, that’s why they were driven to do this,” he said. “We didn’t want it to be a marketing campaign. But this is like Marketing 101 for the next generation of Unitarians.”

Joukowsky and his Unitarian partners are building a national action campaign called “We Defy” around the film’s premiere, which challenges Islamophobia and promotes a more welcoming climate for refugees. The campaign is on track to include hundreds of screenings, solidarity events with Muslim neighbors, public protests and guest speakers from refugee communities.

“In this time of rising racism and scapegoating, Unitarian Universalists are called to stand in solidarity with our Muslim neighbors,” reads an action guide created for the 1,000 or so Unitarian churches across America.

Lead partners include the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA), the product of a 1961 merger that united two of the most progressive religious denominations in America, and the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, which has supported refugees worldwide for the last 75 years and considers the Sharps’ work in Europe to be its first mission.

The UUA counts around 200,000 members in the U.S., though according to the Pew Research Center, approximately 735,000 Americans identify as Unitarian. As mainline Protestant denominations have seen dramatic declines in membership over the last 50 years, the UU membership has stayed relatively steady.

“We’re not struggling so much as treading water against the current,” McDonald said. “Our values are in line with where the culture’s values are. But we’re not for everybody. We’re a religion of choice.”

UUs remain mostly white, at 88 percent, but have made a strong effort in recent years to ally more closely with African-Americans and Hispanics.

“I also see a lot of our congregations really tuned into this moment in history right now,” said Carey McDonald, outreach director of the UUA. “I think about this a lot. What am I going to tell my grandkids about what was going on right now? We’re talking a longer view than just what happens in the next election cycle. We’re working on a different timeline.”

McDonald works from the organization’s modern new headquarters in Boston’s rapidly growing Seaport district. The UUA moved from its historic home on Beacon Street in Beacon Hill in 2014, selling what McDonald called a “huge, untapped asset” in favor of a greener, more accessible space.

The new offices are bright and welcoming, but do not carry the palpable weight of history that the Beacon Street building did. The organization brought some of its most sacred artifacts from the old building, including a bronze memorial honoring the memories of Jimmie Lee Jackson, the Rev. James Reeb, and Viola Gregg Liuzzo, civil rights activists who were killed in Selma, Alabama in 1965.

Jackson was a black voting rights activist killed by an Alabama state trooper. Reeb was a white UU minister from Boston who was beaten to death by local civilians. A few weeks later, Liuzzo, a white UU from Detroit who was shot to death by Ku Klux Klan members.

Though Unitarians’ involvement in the Civil Rights Movement is also sacred to the church, the era created a rift between black and white UUs that never fully healed. In particular, requests and demands of support from black UUs in the 1960s were not approved, causing many black UUs and their allies to leave the church for good.

“There are some things we could have done better in the 1960s,” McDonald said. “We need to not mess this up this time.”

He added that he sees a process of trust building as more black leaders attend the UU General Assembly and more UUs support and connect with the Black Lives Matter movement. More than 100 congregations across the country now hang Black Lives Matter banners on church grounds.

“I was very heartened by how I saw us empowering leaders of color,” McDonald said, referring to this year’s General Assembly in Columbus, Ohio. “We’re very much a religion of the world.”

Though each church operates independently, the UUA provides support and guidance for social justice initiatives related to Black Lives Matter and racial justice, the environment, LGBT rights, reproductive rights, voting rights and refugee assistance.

The All Souls Unitarian Universalist Congregation in New London, Connecticut, Rev. Carolyn Patierno and her 300 congregants decided last year to help resettle Syrian refugees.

Working in a state where Gov. Dannel Malloy has proudly welcomed Syrians fleeing the war, All Souls raised the funds to purchase a house directly next door to the church, which will serve as a halfway house for recently arrived refugees. Families can stay for 3-6 months as they plan a more permanent move.

“This refugee resettlement effort is really a group effort,” Patierno said. “We’re working with five other faith communities. The reason it’s working so well is because we have people from all expertise who are pouring their time and energy into it.”

Patierno said that so far, as long as you don’t count “really nasty comments” on internet news stories about the project, she’s experienced no significant backlash to the house, which is not the case in some other US communities working on resettlement.

“Whatever backlash they might receive, what they’ve been through, how much worse can it be?” she said. “We’re creating an infrastructure that’s going to allow us to settle family after family after family.”

Patierno said her congregation will participate in the campaign around the film, hosting events which will “dovetail beautifully” with the efforts of the congregation and its partners.

Asked why the UUs of New London made this commitment to Syrian refugees, she said, “It was that moment that we have as humans that there’s something we we see in the news that combats the kind of helplessness we can feel. It was that moment where we said, ‘let’s do this one thing that we know we can do.’”

She continued, “Personally, I believe that the religious imperative is to keep hope alive in our hearts and our minds. The first thing we must do is keep that hope kindled and keep ‘overwhelmed’ at bay. When we’re overwhelmed we do nothing. It’s hard to respond.”

A version of this story appeared in the Boston Globe.