This column originally appeared in Navigator, GroundTruth’s newsletter for early-career journalists. You can subscribe to Navigator here.

Editor’s Note: We’re happy to welcome Josh Coe as a guest columnist from this edition of Navigator. Josh is our summer intern and a freelance reporter who publishes regularly for the Boston Globe and recently began contributing to Qiio Magazin, a German-language publication covering tech and society.

Last week ProPublica uncovered a secret Facebook group for Customs and Border Patrol agents in which a culture of xenophobia and sexism seems to have thrived. The story was supported by several screenshots of offensive posts by “apparently legitimate Facebook profiles belonging to Border Patrol agents, including a supervisor based in El Paso, Texas, and an agent in Eagle Pass, Texas,” the report’s author A.C. Thompson wrote.

This is only the most recent example of the stories that can be found by digging into Facebook. Although Instagram is the new social media darling, Facebook, which also owns Instagram, still has twice the number of users and remains a popular place for conversations and interactions around specific topics.

Although many groups are private and you might need an invitation or a source inside them to gain access, the world’s largest social network is a trove of publicly accessible information for reporters, you just need to know where to look.

I reached out to Brooke Williams, an award-winning investigative reporter and Associate Professor of the Practice of Computational Journalism at Boston University and Henk van Ess, lead investigator for Bellingcat.com, whose fact-checking work using social media has earned a large online following, to talk about how they use Facebook to dig for sources and information for their investigations. Their answers were edited for length and clarity.

1. Use visible community groups like a phonebook

While it remains unclear how Thompson gained access to the Border Patrol group, Williams says you can start by looking at those groups that are public and the people that care about the issues you’re reporting.

“I have quite a bit of success with finding sources in community,” says Williams, “people on the ground who care about local issues in particular tend to form Facebook groups.”

Williams uses Facebook groups as a phonebook of sorts when looking for sources. For example, if a helicopter crashes in a neighborhood, she suggests searching for that specific neighborhood on Facebook, using specific keywords like the name of local streets or the particular district to find eyewitnesses. Her neighborhood in the Boston area, she recalls, has its own community page.

Williams also recommends searching through Google Groups, where organizations often leave “breadcrumbs” in their message boards.

“It’s not all of them,” she notes about these groups, “but it’s the ones that have their privacy settings that way.”

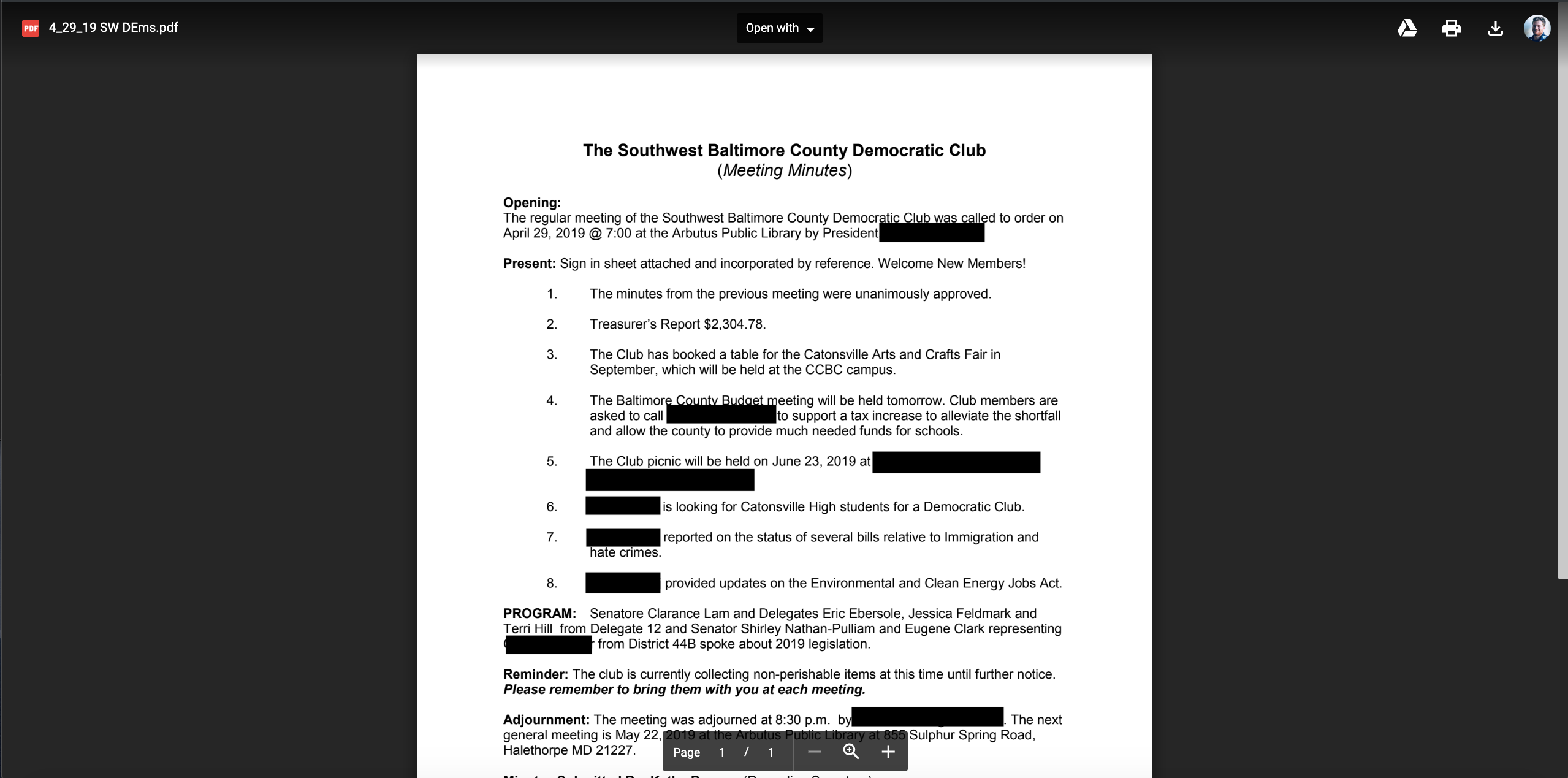

After speaking with Williams, I spent a few hours poking around in Google Groups and discovered a surprising amount of local and regional organizations neglected their privacy settings. When looking through these group messages, I had a lot of success using keyword searches like “meeting minutes” or “schedule,” through which documents and contact information of “potential sources” were available. While you can’t necessarily see who the messages are being sent to, the sender’s email is often visible.

2. Filter Facebook with free search tools created by journalists for journalists

Despite privacy settings, there’s plenty of low-hanging and fruitful information on social media sites from Facebook to Twitter to Instagram, as a 2013 investigation by New Orleans-based journalism organization The Lens shows. The nonprofit’s reporters used the “family members” section of a Charter School CEO’s Facebook page to expose her nepotistic hiring of six relatives.

“But if you know how to filter stuff… you can do way more,” van Ess says.

In 2017, van Ess helped dispel a hoax story about a rocket launcher found on the side of a road in Egypt using a combination of social media sleuthing, Google Earth and a free tool that creates panoramas from video to determine when the video clip of the launcher was originally shot. More recently, he used similar methods as well as Google Chrome plug-ins for Instagram and the help of more than 60 Twitter users to track down the Netherlands’ most wanted criminal.

He says journalists often overlook Facebook as a resource because “99 percent” of the stuff on Facebook is “photos of cats, dogs, food or memes,” but there’s useful information if you can sort through the deluge of personal posts. That’s why he created online search tools graph.tips and whopostedwhat.com so that investigators like himself had a “quick method to filter social media.”

For those early-career journalists who’ve turned around quick breaking news blips or crime blotters for a paper’s city desk, might be familiar with the twitter tool TweetDeck (if not, get on it!), Who posted what? offers reporters a way to similarly search keywords and find the accounts posting about a topic or event.

Here’s how it works: you can type in a keyword and choose a date range in the “Timerange” section to find all recent postings about that keyword. Clicking on a Facebook profile of interest, you can then copy and paste that Facebook account’s URL address into a search box on whopostedwhat.com to generate a “UID” number. This UID can then be used in the “Posts directly from/Posts associated with” section to search for instances when that profile mentioned that keyword.

These tools are not foolproof. Often times, searches will yield nothing. Currently, some of its functions (like searching a specific day, month or year) don’t seem to work (more on that in the next section), but the payoff can be big.

“It enables you essentially to directly search somebody’s timeline rather than scrolling and scrolling and scrolling and having it load,” says Williams of graph.tips, which she employs in her own investigations. “You can’t control the timeline, but you can see connections between people which is applicable, I found, in countries other than the States.”

While she declined to provide specific examples of how she uses graph.tips—she is using van Ess’s tools in a current investigation—she offered generalized scenarios in which it could come in handy.

For instance, journalists can search “restaurants visited by” and type in the name of two politicians. “Or you could, like, put in ‘photos tagged with’ and name a politician or a lobbyist,” she says. She says location tagging is especially popular with people outside the US.

Facebook’s taken a lot of heat recently about privacy issues, so many OSINT tools have ceased to work, or, like graph.tips, have had to adapt.

3. Keep abreast of the changes to the platforms

The trouble with these tools is their dependence on the social platform’s whim–or “ukase” as van Ess likes to call it.

For example, on June 7, Facebook reduced the functionality of Graph Search, rendering van Ess’s graph.tips more difficult to use.

According to van Ess, Facebook blocked his attempts to fix graph.tips five times and it took another five days before he figured out a method to get around the new restrictions by problem-solving with the help of Twitter fans. The result is graph.tips/facebook.html, which he says takes longer than the original graph.tips, but allows you to search Facebook much in the same way as the original.

The next few postings are addressed at nerds only and is my attempt to find out together what happened with Facebook Graph and how to solve it. All tools are down which is a nightmare for #osint community and reporters. Please share this thread so other people can comment on it.

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) June 7, 2019

Even though the site maintains the guarantee that it’s “completely free and open, as knowledge should be,” van Ess now requires first-time users to ask him directly to use the tool, in order to filter through the flood of requests he claims he has received.

I have not yet been given access to the new graph.tips and can’t confirm his claims, but van Ess welcomes investigators interested in helping to improve its functionality. Much like his investigations, he crowdsources improvements to his search tools. Graph.tips users constantly iron out issues with the reworked tool on GitHub, which can be used like a subreddit for software developers.

Ongoing user feedback as well as instructions on how to use van Ess’s new Facebook tool can be found here. A similar tool updated as recently as July 3 and created by the Czech OSINT company Intel X is available here, though information regarding this newer company is sparse. By contrast, all van Ess’s tools are supported by donations.

The OSINT community has its own subreddit, where members share the latest tools of their trade.

4. Use other social media tools to corroborate your findings

When it comes to social media investigations, van Ess says you need to combine tools with “strategy.” In other words, learn the language of the search tool–he shared this helpful blog post listing all of the advanced search operator codes a journalist would need while using Twitter’s advanced search feature.

Williams also had a Twitter recommendation: TwXplorer. Created by the Knight Lab this helpful tool allows reporters to filter Twitter for the 500 most recent uses of a word or phrase in 12 languages. The application will then list all the handles tweeting about that phrase as well as the most popular related hashtags.

Bonus: More search tools

If you want even more open-source tools honed for journalistic purposes, Mike Reilley of The Society of Professional Journalists published this exhaustive and continuously updated list of online applications last month. Be warned though: not all of them are free to use.

Related:

Here’s Pulitzer Prize winner Dave Philipps’ take on using social media in your story.