Detox, Rehab, Relapse, Repeat:

New initiatives but no quick fix

Subscribe to the podcast on iTunes / Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Officer Louise Sanfilippo of the 122nd Precinct on Staten Island remembers the first time she brought someone back to life. She was responding to a 911 call from a shopping center on the island’s South Shore. When she arrived, she saw a man pacing. He pointed to a parked car. Inside, there was an unconscious man with a needle stuck in his arm. He was turning blue.

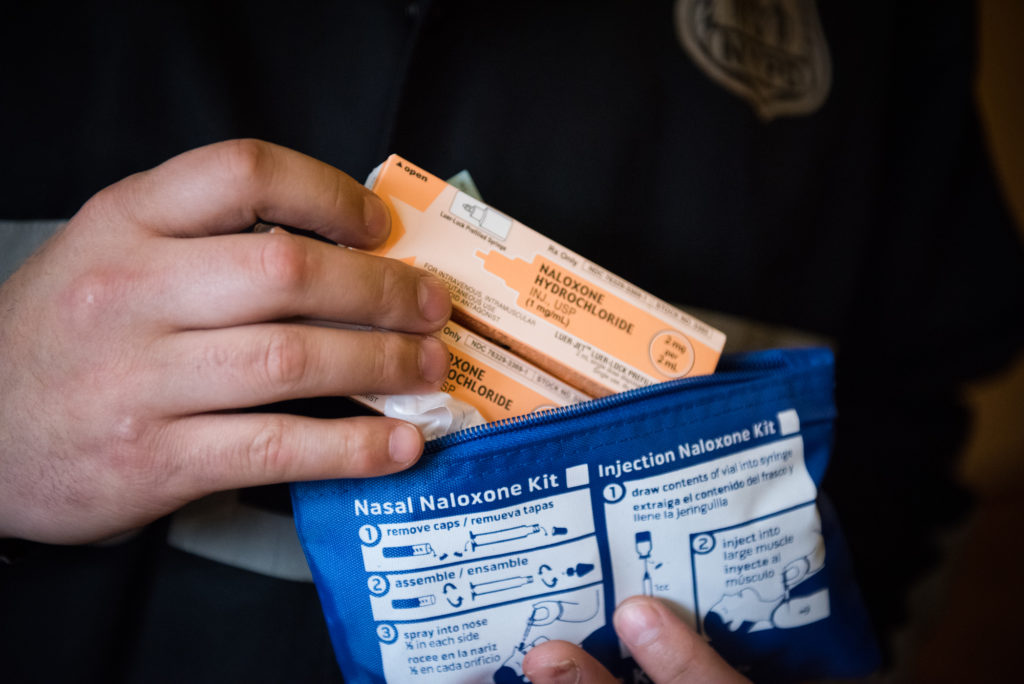

Officer Sanfillipo reached for her Narcan, a nasal spray that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. She sprayed the drug into each one of the man’s nostrils, and his eyes blinked open.

Since that day, Officer Sanfillipo says she has saved 13 lives with Narcan, one of the brand names for naloxone. The opioid epidemic is so bad on Staten Island that she says she can’t do her job without the lifesaving medication on her belt.

“I don’t know what the future’s going to hold – if this problem is going to heal or get any better,” she says. “But I can say that I wouldn’t go out on patrol without taking the naloxone with me.”

Over the past several years, Staten Island has competed with the Bronx for the highest rate of overdose deaths from heroin and other opiates in New York City. To respond to the crisis on Staten Island, community leaders have pioneered new ways to help people get into treatment. But despite their efforts, people keep dying.

“As more and more bodies were piling up, literally, we knew that something had to get done,” says Karen Varriale, the narcotics bureau chief at the District Attorney’s office.

As more and more bodies were piling up, literally, we knew something had to get done.

Nacrotics Bureau Chief at the District Attorney's Office

Varriale helped launch a program that allows low-level drug offenders to bypass the criminal justice system and go straight into treatment. It’s called HOPE — Heroin Overdose Prevention and Education — and it’s one of three programs in the country. If defendants check into treatment within 30 days of being arrested, their court case disappears like it never happened. Varriale is hoping this new approach can save lives. She says the opioid problem is so bad here that people are dying before they even make it into court.

“Our overdose rates are sky high,” says Varriale. “You have to treat the addiction to keep people from either dying or from committing other crimes.”

This is a paradigm shift for law enforcement on Staten Island. Drug addiction is now seen as a public health problem – not simply a criminal justice issue.

But even as the punitive approach to drug treatment changes on Staten Island, the stigma of addiction remains.

“The vast majority of folks that struggle with addiction either end up incarcerated or in some court-mandated or [court-ordered] process,” says Dr. Harshal Kirane, director of addiction services at Staten Island University Hospital. “We have yet to incarcerate diabetics for eating too many chocolates, or folks with hypertension for smoking cigarettes. So that highlights how addiction is mired in stigma.”

On Staten Island, the stigma has kept many residents in denial about just how bad the opioid crisis is here. Adrienne Abatte, who runs Staten Island Partnership for Community Wellness, works closely with residents and treatment providers on the island.

“When we first started doing presentations at community board meetings and at schools, people were like, ‘Oh, that’s awful, but that’s not here. That’s not my problem – not my kids,’” she says.

Abbate says the denial also makes it difficult to educate the community about how to treat an addiction to opioids. Many Staten Island residents go off-island for treatment, sometimes with mixed results. Abbate and other treatment providers on Staten Island say that many residents believe the typical 28-day rehab, which is often covered by insurance, is a cure-all for addiction. But it’s not, she says.

“Twenty-eight days is not long enough,” says Abbate. “And you’re released back into your community without connections to support groups or programs. And then you go right back into your old circles.”

All too often, once people go back into their old circles, they relapse, Abatte says. And after treatment, these relapses can be fatal if drug users use the same amount of heroin or other opiates as they did before treatment – when their body had developed a tolerance to the drug potency.

To guard against relapse, Abatte encourages people to get treated locally and to make a plan for care once they return home from treatment. She wants residents to know that addiction is a chronic illness – one that requires long term care.

You don’t want to treat addiction. You want to prevent addiction.

Staten Island University Hospital'

On the south side of the island, Staten Island University Hospital has piloted a new initiative to plug opioid users into ongoing treatment for addiction. By offering on-demand detox services and addiction medications like methadone and suboxone, as soon as someone walks into the hospital, the healthcare providers hope to close the deadly window between rehab and relapse. The new effort is led by Dr. Kirane.

“You don’t want to treat addiction. You want to prevent addiction. Similarly, here, you don’t want to treat overdose — you want to prevent overdose,” says Dr. Kirane.

Many addiction specialists consider methadone and suboxone the gold standard for addiction treatment. Studies show that the drugs can dramatically reduce overdose rates. Dr. Kirane’s new program fast tracks the process of getting on methadone or suboxone, but Dr. Kirane doesn’t understand why Staten Islanders aren’t flocking to the hospital to get these medications.

But Adrienne Abbate has a hunch: On Staten Island, there’s a stigma surrounding these medications. Abbate says the problem is that many of the people living on Staten Island are suspicious of opioid-based prescription medications. Both methadone and suboxone are opioids, like prescription painkillers and heroin.

“One of the pieces of stigma, and I can understand it is that people feel like, ‘Well, pharma got us in this in the first place. Now, you’re coming up with another drug,’” she says.

After all, it was prescription painkillers that led to Staten Island’s opioid crisis.