The History You Never Heard:

How heroin became an inner-city epidemic

Subscribe to the podcast on iTunes / Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

St. Ann’s Avenue and 139th Street is nondescript, as far as corners in the South Bronx go. The buildings are mostly brick, five-floor walk-ups with jutting fire escapes. There are a couple of bodegas and a pawn shop within throwing distance.

On the northwest corner, plastic posts hold up a red tent, like you’d see at a farmer’s market. Under the tent, four middle-aged men and women sit in folding chairs. They’re bundled up for the weather in a motley blend of sweatshirts, coats and hats.

Above them is a banner that reads: St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction.

St. Ann’s Corner is a South Bronx nonprofit that works with intravenous drug users. They have a brick-and-mortar facility about a mile from here where they offer a gamut of services, from acupuncture to group therapy. But their core service is the needle exchange program they’ve been running at this corner since 1990. Here, they can give clean needles and overdose reversal kits directly to the community that needs them.

Among those gathered under the tent, Deborah Watkins has been with St. Ann’s the longest. When she first came out here 25 years ago, the community garden they set up in front of was a burned-out lot.

“You ever see one of them dirty lots where they just throw garbage in ‘em? No fence. No trees. No nothing,” she says.

Watkins is 56 years old and slight, with dark, creased skin and glasses. But when she tells the story of how St. Ann’s Corner came to be, she crackles with energy. She talks fast, punctuating her statements with “d’you understand?”

St. Ann’s sets up on this particular corner because, for decades, this has been the epicenter of the drug trade in the borough.

Before a police crackdown in the mid-’90s, the drug dealers ran this place like an open-air bazaar. The murder rates were among the highest in the city, as were the rates of drug-related deaths – overdose and HIV.

By 1990, half of all New York City’s intravenous drug users were infected with HIV. The National Academy of Sciences estimates that tally as high as 100,000 people, if you include those who had already died by that same year. And the South Bronx had the second-highest rate of AIDS, after Manhattan.

Syringe exchange programs in Europe, Hawaii, and New Haven, Conn., had already been shown to lower HIV rates by that time. But needle exchange was illegal in New York City. Then-Mayor David N. Dinkins said it condoned drug use. If a person got caught passing out syringes, they’d be arrested.

Breaking the law to save lives

But not everyone could just stand by and watch. The founders of St. Ann’s came out to this corner in 1990 and convinced the local drug dealers to let them pass out needles from the trunk of a car – illegally. Deborah Watkins was around for those Wild West days.

“We were here, and the drug dealers were here, and we got along great,” she recalls. “We left the park nice and clean, so it wasn’t like you had to worry about kids coming by and picking up dirty needles, you understand?”

Cleaning up the block was key. Without the city to back them, St. Ann’s had to get the locals on their side. Within three years, needle exchange was legalized. But the spectre of those days remains.

“Once in awhile, I still run across somebody who’s like ‘you’re promoting drug use,’” says Tino Fuentes, a director at St. Ann’s. “Then I tell em, ‘No, no, no, I’m promoting life.’”

Fuentes is 56 years old and used to sell heroin back in the 1980s. In his leather jacket and newsboy cap, it doesn’t take a surplus of imagination to picture him running a corner like this one 30 years ago.

“It’s just a shame that people think that somebody’s life is better than somebody else’s,” he says.

Fuentes does his best to make sure that the booth is stocked with more than just drug paraphernalia. On some days they have canned goods available. And prophylactics.

“You can walk by and get condoms, if you happen to be lucky,” he says.

It’s just a shame that people think that somebody’s life is better than somebody else’s.

St. Ann's Corner

It’s important for Fuentes that their tent be seen as more than a place for just drug users.

“Cause there’s still that stigma – people say ‘these people,’ which I hate that. We have people that are diabetic that come here ‘cause insurance won’t pay for the syringes, you know?”

Later that same day, an elderly diabetic would indeed come by and exchange hundreds of needles.

HIV rates have fallen drastically since 1990, largely due to needle exchange programs. But this neighborhood still has one of the highest rates of HIV in the city, and overdose rates are higher than they’ve ever been. The rate of overdose death in the Bronx jumped by nearly 50 percent between between 2014 and 2015 – from 170 bodies to 252 – with the vast majority involving opioids.

The official numbers for 2016 aren’t in yet, but officials expect the number of overdose deaths in New York City as a whole to surpass 1,200 – more than double the number of murders and traffic deaths combined.

So St. Ann’s continues its work. They keep track of their clients, or “participants” as Fuentes calls them, not by name but by assigning them a card and an ID number. That anonymity is integral – no one here can afford to be branded a heroin addict or a junkie. Such a mark could get them fired or kicked out of public housing.

An estimated 20 million people in the United States have a substance use disorder, according to an annual federal survey. The majority are struggling with alcohol dependence, but for a growing number of people, the substance is an opioid – either prescription painkillers or heroin. That means a lot of the country is becoming a little more like the South Bronx – more familiar with needles, overdose and death.

And stigma.

Charting the history of Stigma

But why, exactly, do opioids carry so much baggage?

This is a question being explored by Dr. Samuel Kelton Roberts, a professor of history and sociomedical studies at Columbia University. He’s writing a book on the history of drug addiction and public policy.

He says it’s important to understand that the stigma surrounding opioid addiction wasn’t always there. A hundred years ago, opioids like morphine and heroin weren’t even regulated.

“Because it was unregulated, it was also unstigmatized – or had not yet been stigmatized,” says Roberts. “I’m not saying that there were people were shouting from rooftops, ‘I’m a Laudanum addict,’ you know, or ‘I’m a hop fiend,’ but I think it was a pretty common use.”

During the 19th and early 20th century, anyone could walk into their neighborhood pharmacy and grab a bottle of Bayer’s patented heroin cough syrup, right off the shelf.

Morphine tonics were touted as a cure-all for everything from indigestion to insomnia. Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup was marketed to mothers as a way to soothe teething babies.

“I think it was a pretty common use amongst the classes of people that today we assume to be entirely law abiding, which is to say, middle class white people,” Roberts says.

Eventually, a noticeable rise in opioid dependency and a burgeoning federal regulatory movement lead to anti-narcotic laws. The 1914 Harrison Act strictly regulated how narcotics could be dispensed, and by 1919 it was illegal for doctors to prescribe opioids for anything but pain.

This is when the stigma developed. Once opioid use is criminalized and opioids become a black market drug, “all opioid users are criminals,” Roberts says.

“For the next, you know, several decades, a lot of our public policy – and our research by the way – is guided by the assumption that there is something developmentally, psychologically, even morally pathological among people who use opioid drugs,” he adds.

In other words, the belief that only certain kinds of people are susceptible to addiction.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, it was poor working class white immigrants who bore the brunt of that stigma. Soon after that, it became people of color.

By the 1960s, heroin was a part of daily life in the South Bronx. Manufacturing jobs had disappeared soon after World War II. White flight followed. And as the black market for drugs like heroin became a way to make a living, the Bronx became a place to buy drugs – and take them.

By the 1970s, property values were so low in the South Bronx that the insurance policies were often worth more than the buildings. So some property owners torched their own buildings and infrastructure began to collapse. In response, the city pulled back resources.

“There’s basically one hospital at this time” in the area, Dr. Samuel Kelton Roberts explains. “There were rare tropical diseases that people were finding [in the Bronx] – even tuberculosis.”

By the 1970s, the Lincoln Hospital building had been condemned, but it was still operating. The emergency room teemed with rats, and children would go in for care and come out with lead poisoning.

“Despite being in one of the most heavily affected regions of the city for heroin, it has no addiction treatment programs – none at all,” says Roberts.

In 1970, the revolutionary Puerto Rican nationalist group Young Lords, took over the hospital. They allied with some of the health care workers and effectively occupied the space. One of their demands was a drug treatment program, and the city granted it. It’s a potent memory for the workers at St. Ann’s, who see their efforts as a continuation of that community activism.

“These were all people who did something because the system wasn’t doing it for us. Somebody decided enough is enough,” says Tino Fuentes.

A number of drug treatment clinics opened up in and around the Bronx the 1970s, and New York City became one of the few places in the country relatively well-equipped to treat opioid addiction.

Despite being in one of the most heavily affected regions of the city for heroin, it has no addiction treatment programs – none at all.

History and Sociomedical Studies at Columbia University

The main treatment: methadone. Another opioid. But a milder, longer-acting one. Methadone provides prolonged relief from withdrawal but without inducing as much of a high as heroin. When properly dispensed, it’s known as medically assisted treatment. It’s also known, derisively, as a replacement therapy. But it is one of the few treatments that allows addicts to live safer and less attenuated lives.

Because of intense federal regulation, methadone isn’t dispensed at any doctors’ offices. There are special places for methadone clinics – usually off the beaten path. Given the stigmatized clientele, the clinics became stigmatized as well.

By the end of the 1970s, public backlash forced many clinics to close, sending thousands of addicts back to street drugs.

But methadone helps keep a lot of people sober, including Ivan Flores.

Memories of shooting galleries

“People called us bums, useless,” says Flores, a South Bronx native.

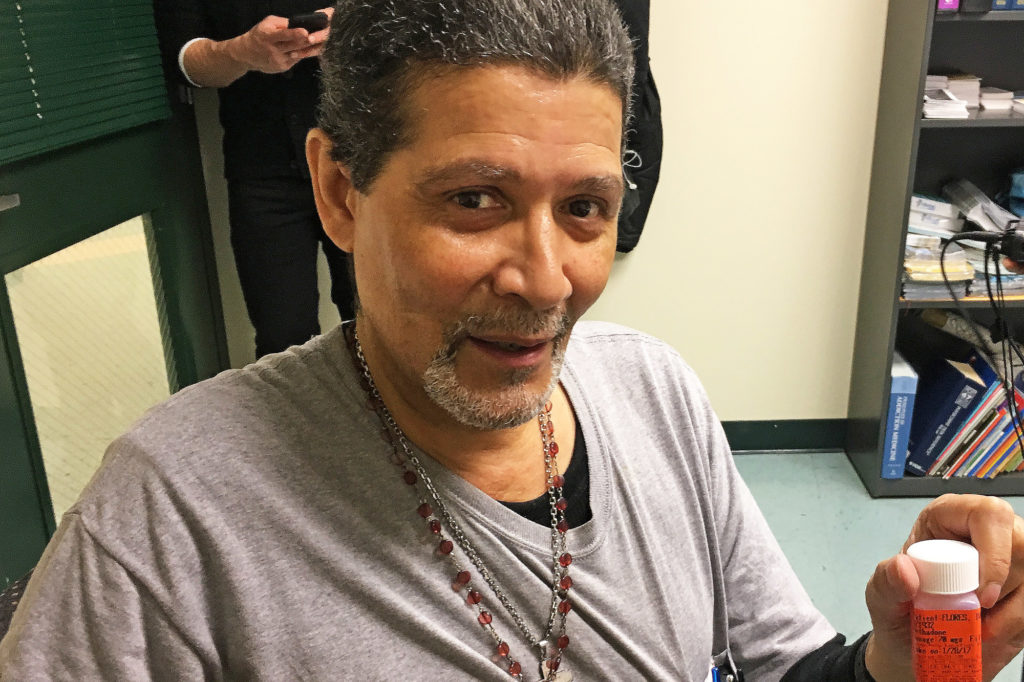

Sitting at a diner in a sweatshirt and jeans, with a number of Catholic pendants hanging from his neck, he could be mistaken for a man in his forties. But when he stands up, his cane betrays his 61 years. Three decades of heroin addiction made for a life hard lived.

When Flores was a kid, his mother sent him upstate to get him out away from the Bronx. He made into a private high school on a basketball scholarship. But he partied too hard there, struggling in school as a result, and ended up back in the Bronx, getting lost in cocaine and heroin.

(Photo by Michael O’Brien/GroundTruth)

The main problem, he says, was feeling supremely uncomfortable in his own skin. Like many addicts, he has a history of childhood trauma. He had been sexually abused by a family member.

“Dealing with that was one of the reasons, the issues, that I got high,” he says.

By the 1980s, getting high in the South Bronx often meant nodding out in a shooting gallery. These were vacant buildings – which were abundant in this neighborhood – commandeered by local drug dealers.

Flores recollects the first time he ended up in one of those places, in 1983.

The windows were boarded up, with just a little bit of light peeking through. There was a man sitting at a desk, surrounded by candles. Flores gave him a dollar and was handed a needle. He had to give it back when he was finished, so it could be rented by the next person.

At that time, HIV was already rampant among intravenous drug users. Flores was relatively lucky – he only contracted Hepatitis C. Clean needles could have prevented that.

It would take 10 more years for the city to allow needle exchanges. In 1993, St. Ann’s became the fifth needle exchange to be authorized by the city. But by then, more than 40,000 New Yorkers had died of AIDS – likely around half of them due to IV drug use.

Breaking the law (again) to save lives

Back on the corner of St. Ann’s and 139th Street, Tino Fuentes has trouble getting one image out of his head – in the shooting galleries, the needles would sit in pickle jars filled with water, dyed pink from blood.

“Now that I think about it, it’s horrible,” he says.

It’s part of what motivates him to do the work he does.

Much of the rise in opioid death is due to what heroin is being mixed with: fentanyl. It’s a cheap, synthetic opioid, dozens of times more potent than heroin. If an adult can overdose on 30 milligrams of heroin, it takes only 3 milligrams of fentanyl. That’s the equivalent of just a few grains of kosher salt. Such a potent opioid is easier to smuggle, but harder to evenly distribute in each bag of street drugs.

Fuentes and his team got their hands on testing strips that can detect fentanyl in heroin. And out on the streets, they’ve been teaching drug users how to use them. In some cases, Fuentes is testing bags of heroin himself. When he finds that a bag tests positive for fentanyl, that information is posted at St. Ann’s. It’s a way of getting the word out.

Fuentes hopes that if drug users suspect they’ve a bag laced with fentanyl, they’ll take extra precaution.

“They’re not gonna throw away their shot, but they’d know not to do the whole bag,” Fuentes explains.

And much like the early days of needle exchange, Fuentes is risking arrest. Just holding a bag of heroin is illegal, so testing heroin for fentanyl on a drug user’s behalf is illegal too. But Fuentes sees this work as essential.

“Nobody should die because of drugs. I’d rather get arrested than see somebody dead,” he says.

Out of the 29 test results he’s seen so far, Fuentes says all but three of those 29 bags of heroin came back positive for fentanyl.

This aligns with what the city health officials are seeing. They’re in the midst of conducting their own citywide survey on fentanyl in the drug supply. That data isn’t available yet, but according to Dr. Denise Paone with the health department’s Bureau of Alcohol and Drug Use Prevention, Care and Treatment, drug users should take extreme caution.

Nobody should die because of drugs. I’d rather get arrested than see somebody dead.

St. Ann's Corner

“We believe that fentanyl is becoming ubiquitous in the drug supply in New York City and are advising people who use drugs to take ‘universal precautions’ against overdose, regardless of the results of a drug test,” Paone told me over email. “These precautions include using with someone else, taking turns using drugs, using a small amount to test strength, carrying naloxone and avoiding mixing drugs.”

Fentanyl isn’t only found in New York City. It’s partly responsible for the rise in overdose deaths across the country. That rise is also due to the sheer number of people who are addicted to opioids.

Many of those people are now middle class, suburban and white. And something else is new too – the opioid overdose epidemic is now officially considered a public health crisis.

Fuentes thinks those two facts are related.

“It’s always been a public health issue. It just wasn’t affecting the right people. But now I guess it is,” he says. “How many lives have been lost – whether literally through death or through incarceration? But now it’s a public health issue.”