A Better Way to Treat Addiction:

A new standard of care in the South Bronx

Subscribe to the podcast on iTunes / Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

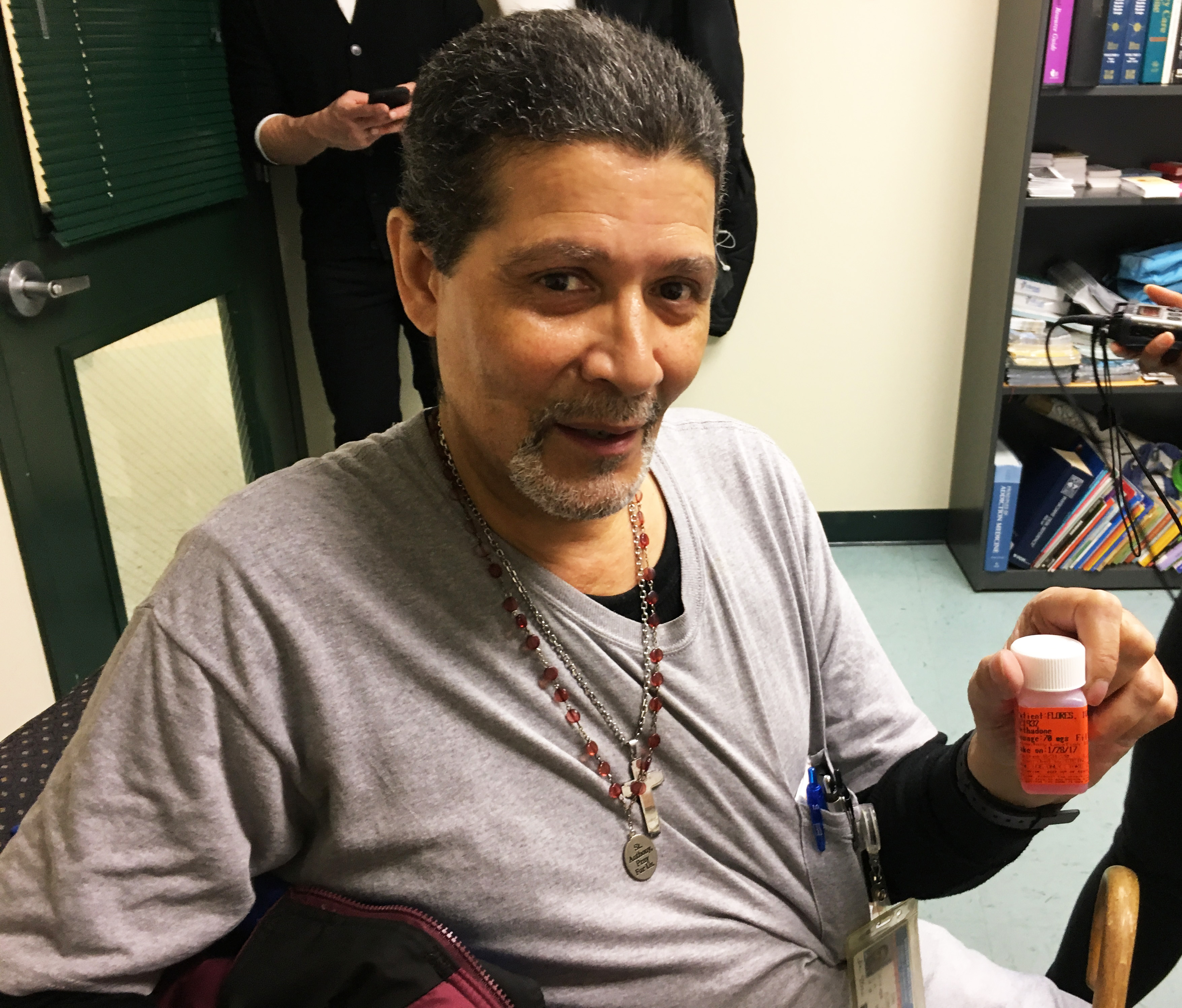

Ivan Flores, 61, started sniffing glue when he was 7 years old. Then, about 20 years later, he began shooting heroin and used the drug for over three decades.

“It started out as fun and that fun became a nightmare pretty quick,” he said.

Ten years ago, Ivan finally quit. He credits his sobriety to Montefiore Hospital’s Wellness Center at Port Morris, a methadone clinic.

“If it wasn’t for the program, I would be dead – seriously, the way I was going,” said Flores. “[Now] I’m able to spend time with my family, my kids.”

The Wellness Center at Port Morris looks like a typical methadone clinic. It’s in an isolated area of the South Bronx, almost underneath a major freeway, and it’s surrounded by commercial buildings. The clinic treats about 1,100 patients and most are poor people of color on Medicaid, and some are homeless or mentally ill. The majority come to Port Morris everyday to take their daily dose of methadone, which is dispensed by a nurse.

But Port Morris is different from other methadone clinics. Here, patients receive primary and comprehensive medical care, plus support services.

“I’m able to deal with a lot of issues – not just my drug addiction, but my other health issues,” said Flores. While he was using heroin, Flores contracted Hepatitis C from an infected needle. He was put on a drug regime that cured the disease and also attended support meetings at Port Morris. Doctors at the clinic referred him to Montefiore Hospital for heart surgery and to get his knee replaced, too.

“It’s like a one stop shopping center. If you want to get clean, this is the place to come,” he said.

Port Morris and Montefiore’s two other Wellness Centers have adopted a growing movement in the medical community – treating opioid dependence as a chronic disease. Dr. Melissa Stein, the medical director, said the goal is to manage addiction so that patients can lead productive lives, just like people who have diabetes or high blood pressure. This unusual approach to addiction treatment has been effective. According to hospital administrators, the program’s retention rate is higher than the standard set by the state and patients are less likely to relapse than those in other methadone programs.

“Stability is really clutch,” said Stein. “Staying out of the hospital, staying healthy, staying abstinent, staying sober – that’s an incredibly worthy goal, and it’s greatly underrated in our culture.”

In the mid-’60s, New York City was the first place to use liquid methadone to treat opioid addiction. Doctors who created the synthetic drug found it worked longer and more effectively than other treatments at the time, including morphine.

By the early 1970s, methadone clinics popped up around the city. The drug was highly regulated and locked in a safe before it was dispensed. Then came the stigma and an assumption that a methadone user is still a drug user. Addicts seeking help were treated like criminals and residents resisted housing the clinics in their neighborhoods. The clinics that did exist were kept out of sight and placed in run-down buildings in seedy, isolated, crime-ridden areas. Methadone users were seen as pariahs.

But Port Morris seems to be an oasis for patients on methadone. There’s job counseling, peer meetings and even a creative writing group that has published two books. But despite the community model, Dr. Stein said methadone treatment still gets a bad rap. The perception is that methadone clinics are “a lot of drug addicts all together getting more drugs,” said Dr. Stein. “I would actually go so far as to say that the word ‘prejudice’ is more appropriate than stigma.”

One of the downsides of methadone is that patients have to go to a clinic everyday to take their dose. This can be a deterrent to people who want to seek treatment, but don’t want to be tethered to a clinic.

In 2002, the FDA approved a new treatment for opioid addiction, buprenorphine, also known as suboxone. Suboxone is highly regulated, too, but unlike methadone, it’s prescribed by a doctor and can be picked up at a pharmacy. The medication is like birth control pills or high blood pressure medication – it can be taken in private.

Dr. Chinazo Cunningham runs the addiction treatment program at Montefiore’s Comprehensive Health Care Clinic on the other side of the South Bronx. Ten years ago, the clinic was one of 10 health centers in the country to receive federal money to integrate suboxone into primary care. Dr. Cunningham became one of the first primary care physicians in the country to be licensed to prescribe the medication.

Today, most of the primary care doctors at Comprehensive Health Care Center prescribe suboxone. They, along with Dr. Cunningham, have a special license from the DEA and can only treat a limited number of patients by law. Nationwide, only about 3 percent of primary care doctors actually prescribe the drug, even though many consider it to be the standard of care for addiction treatment. Dr. Cunningham said that the stigma of addiction extends to her colleagues, who say they don’t want “those” patients in their waiting rooms.

“My response is – quote, unquote –‘those patients’ are already in your waiting room,” said Dr. Cunningham. “They are your colleagues, your patients, your neighbors, your friends and your family members, because addiction does not discriminate.”

Dr. Cunningham has also spearheaded an outreach program to teach community members how to use naloxone, the life-saving overdose reversal drug, while they sit in the clinic’s waiting room. The rest of New York City is following suit.

If a person is interested, they go through a short training to learn how to administer the drug, then they take receive a free kit. The small blue kit contains two doses of the life-saving medication. Yaritza Holguin, a community health worker, teaches the Narcan training. She said the response to the Narcan has been mixed.

“They see this in their communities and it has had an impact on their lives, and they’re very happy to receive this kit,” said Holguin. “But some people are a bit resistant because there’s a lot of stigma surrounding substance abuse, and they don’t want to be connected to it or related to it in any way.”

Since the launch of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 and the expansion of Medicaid benefits to tens of thousands of people across the country, Montefiore Health System and other hospitals have been able to expand addiction treatment and prevention services. Dr. Cunningham said that even with the additional funding, overdose death rates continue to rise.

“There is no silver bullet. There is no one answer. It has to be like all hands on deck to really bend this [addiction] curve. The epidemic is only getting worse.”