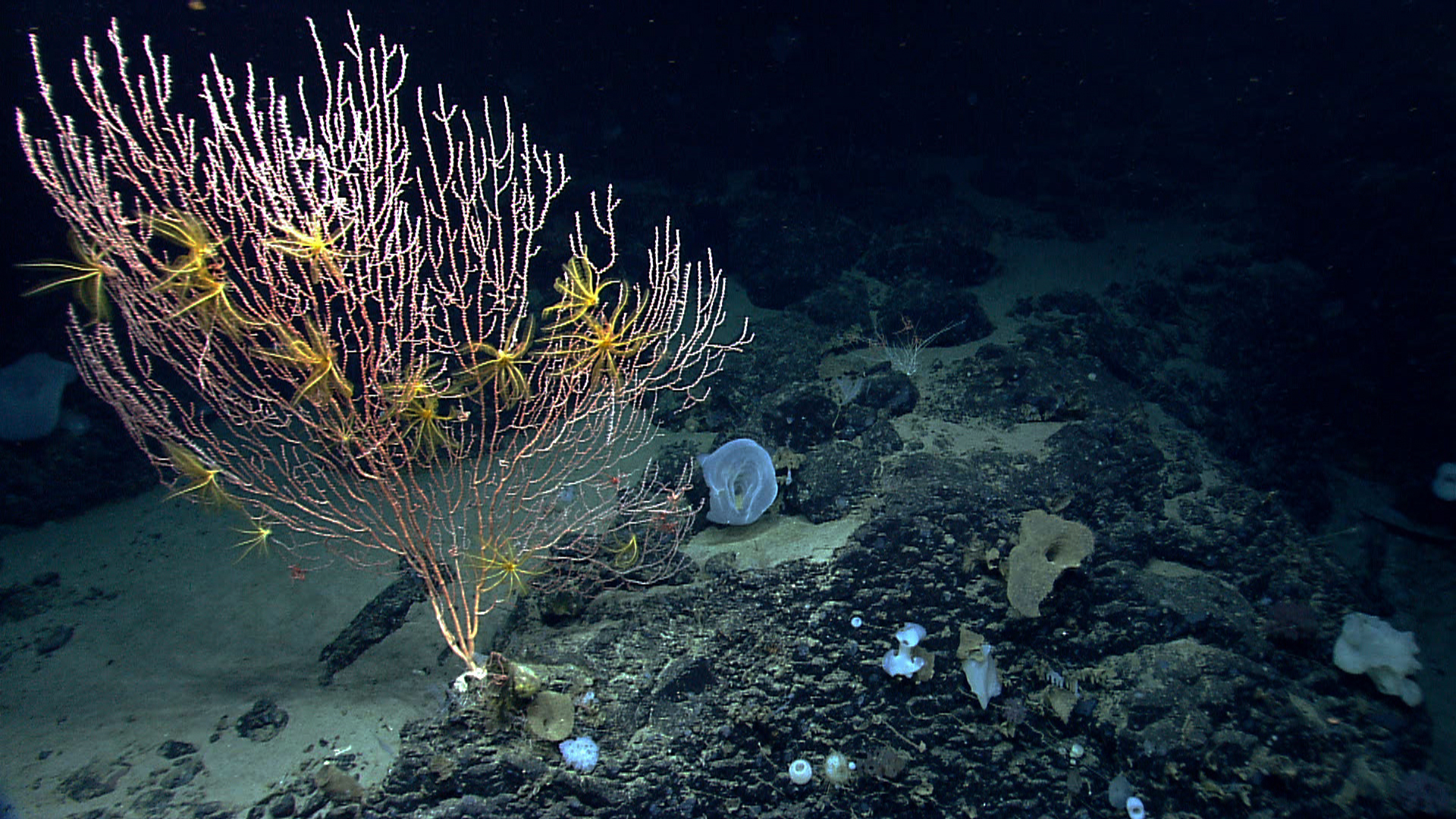

BOSTON — For a marine scientist, the ancient corals found in the Atlantic Ocean compare to the towering trees of the Redwood National Park.

Like the famous trees on the West Coast, corals can live for a thousand years but are sensitive to outside disturbances. Peter Auster, a research scientist with the Mystic Aquarium and the University of Connecticut, said the corals create a foundation for marine life by providing habitats and food for other species.

“There are species that live exclusively on different species of deep sea corals,” Auster said. “And so if you eliminate the corals, there’s cascading impacts to other species.”

Scientists have identified at least 73 types of corals in the area now known as the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, the only marine monument in the U.S. Atlantic Ocean. The 4,900 square miles of ocean contain some of the most biodiverse habitats in the Atlantic and has been the center of controversy since its designation by President Barack Obama in September 2016.

Conservationists say it should be protected because of the high level of biodiversity in a relatively small area of the Atlantic. But members of the fisheries industry say the designation came without much input from the affected community.

Creating the national marine monument

During his eight years in office, former President Obama protected more than 550 million acres of public land and water as national monuments under the 1906 Antiquities Act. Unlike creating a national park, which requires an act of Congress, a president can declare a national monument to protect “objects of historic or scientific interest” with a proclamation.

Critics of the monument say President Obama overstepped the powers set forth by the Antiquities Act and did not provide enough opportunity for public comment. In April, President Donald Trump signed an executive order asking his Secretary of the Interior, Ryan Zinke, to conduct a review of 27 monuments created since 1996. The purpose of the review is to determine if these monument areas qualify under the terms of the act and to address concerns from the community.

Two days later, Trump signed another executive order outlining his “America-First Offshore Energy Strategy.” The plan demonstrates Trump’s vision for the exploration and production of energy on federal lands and waters to decrease America’s dependence on foreign energy.

Priscilla Brooks, the director of ocean conservation at the Conservation Law Foundation, said marine monuments are important for protecting ocean life as companies look to harvest natural resources from previously untapped sources. The monument designation protects the area from commercial extractive activities that could potentially harm the habitat, including fishing, mining and drilling.

“Increasingly we’re looking to conduct oil and gas drilling everywhere in our ocean,” Brooks said. “We are looking to the sea floor to provide sand and gravel to shore up our coastlines and for all the construction we’re doing. We’re using our oceans a lot more and so this is an attempt to protect these places while we still can, while they’re still pristine.”

The heart of it is, we recognize we want to protect corals but we recognize we want to protect fishing. And how do we we sort of balance those two things?

“These kinds of designations like Yellowstone National Park or Yosemite are gifts to the American public in perpetuity,” Auster said. “This is the only place in federal waters of the U.S. Atlantic that is protected in perpetuity for conserving our natural heritage, our biodiversity of our oceans and U.S. waters.”

Since the review of the monuments was announced, Zinke has been visiting each of the sites to speak with various interest groups and community leaders. The comment period on five marine national monuments and six marine sanctuaries will remain open through August 15. Zinke is expected to make his final recommendations to the president at the end of this month.

Fishing industry’s concerns

Captain Fred Penney, a lobsterman out of Boston Harbor, believes that the monument will hurt the future of fishing in New England because the new restrictions were implemented without much input from the fishermen themselves.

“To have no regulations and have it be a free-for-all, that’s completely unacceptable, I understand that,” he said. “I wouldn’t want to see that. But what they’re doing now doesn’t seem to be it.”

Many in the industry felt fishing in the area should have been regulated under the Magnuson- Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act, which created eight regional fishery management councils to maintain sustainable fisheries and habitats in the U.S.

Fishermen argue the council’s lengthy public process is more transparent than a proclamation from the president and allows for more input from the community.

John Williams of the Atlantic Red Crab Company said the fishermen were not given much notice about meetings and the scope of the monument. He argued the area was thriving under the council’s management before the monument designation.

“We’d been in there for 40 years and if it’s… pristine now, after our presence for 40 years, why is there an emergency for the president to use an act to protect this thing?” Williams said. “Why not give it to the council and let the council do its job?”

Before the Obama administration announced the monument, the New England Fishery Management Council was working on a coral amendment that would protect deep sea corals, one of the goals of the monument. The South and Mid Atlantic Councils passed similar regulations years earlier.

The restrictions would prohibit certain types of bottom trawling fishing gear and limit fishing below 600 meters along the Atlantic coast, including in the canyons and seamounts.

For many, the monument announcement came as a surprise because the fishery councils were already working to protect the area.

Michelle Bachman, a fishery analyst with the New England Fisheries Management Council, said the council worked with conservationists concerned with preservation and fishermen who work in the area while creating the amendment.

“The heart of it is, we recognize we want to protect corals but we recognize we want to protect fishing,” she said. “And how do we we sort of balance those two things?”

Fishing groups challenge monument designation in court

In March, five New England and Atlantic fishing organizations collectively sued the federal government for access to the monument area.

The lawsuit alleges that the Obama administration ignored its responsibility to the community and economy in establishing the monument.

Beth Casoni, executive director of the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association, said the frustration with the monument has to do with the methodology the administration used. The MLA is one of the plaintiffs in the case.

“This will challenge the legality of the use because when the Antiquities Act was created, it was for lands owned by the government,” Casoni said. “There was nothing further than the three mile line that they considered their land and this is 180 miles offshore.”

The lawsuit is stalled in the court system until Zinke completes his review of the monuments.

“Between the lawsuit and President Trump, hopefully something will get done,” Penney said. “And at least make it so that these guys can make a living out there. And I mean, not for nothing, but when was the last time you were out there? Nobody goes out there. Nobody.”

Conservation groups want more protections

But conservations and scientists familiar with the area say the Magnuson-Stevens Act would not provide the same protections as the monument because it only regulates fishing. It would not protect the area from other extractive activities like mining and drilling.

“The Antiquities Act is not about managing fisheries, the same as it is not about managing forest resources,” Auster said. “It’s about conserving areas that are sensitive and vulnerable for historic and scientific purposes.”

The boundaries of the monument went through several drafts before the current configuration was chosen. The area up for consideration was reduced by 60 percent from the original proposal. Additionally, the lobster and crab fisheries were given seven years to phase out their operations in the monument.

Beyond protecting the species and habitats in the canyons and seamounts, the designated area would also allow scientists to study the effects of climate change in the ocean.

“This would be the one place that would serve as a real reference site to know, well is this change due to fishing, is this change due to climate change, is this change due to some other cascading factor in the lives of the animals that are a part of these communities,” Auster said. “This would be the one place you could go to know that at least the direct human impacts are not occurring.”

For now, action on the monument is stalled while Zinke completes his review. But Auster says Zinke’s recommendation will not be the end of the discussion. The outcome of the review and any potential court action could set a precedent for the president’s ability to use the Antiquities Act to protect federal land in the future.

“I would imagine on however this comes out, legal challenges will emerge,” Auster said. “There’s nothing wrong with either perspective, it’s just we want to be able to do both.”