SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico and NEW YORK — The word is pa’lante

In Puerto Rican culture, from the island to the Bronx, it is steeped in meaning, and roughly translated from Spanish as “forward” or “onward.” It was coined as street slang amid the community activism and fight for Puerto Rican self-determination that grew out of Spanish Harlem in the late 1960s. These days the word has become less about radical politics and more about economics and resiliency.

These days, pa’lante is about a new generation of Puerto Ricans recognizing that their spirit of moving forward, of hustling and persevering, is an important collective culture train that is much needed as the economy of Puerto Rico is in a historic meltdown.

The territory of one of the wealthiest countries in the world is now teetering on bankruptcy and hoping for a bailout during hearings which are underway this month in Congress. The Puerto Rico’s economic relationship with the mainland has become increasingly unfavorable in recent years, contributing to one of the largest population exoduses in the Western Hemisphere.

With a relatively high cost of living, an oppressive level of debt and a 60 percent unemployment rate, Puerto Rico is losing the next generation of its middle class to the U.S. in a “brain drain.” And a new surge of immigration has begun.

Juan Cordoba, 22, is a fifth-year geography student at the University of Puerto Rico and said he doesn’t see a future for himself or his peers at home.

“I don’t see people having hope,” he said. “It’s not that people are choosing to leave, but they are obligated to leave. ”

But life is also tough for a generation of Puerto Ricans growing up in The Bronx, still the largest Puerto Rican community in the U.S., and the hub of Nuyorican culture. In both places, this is a generation that operates upon the idea of pa’lante, to hustle every day despite long odds of economic prosperity.

The use of the word pa’lante came from the name of the Young Lords’ newspaper, a vehicle to promote change for Puerto Rican communities living under oppression in New York City in the 1970s.

The mentality of pa’lante also represents the ideas that Puerto Ricans are already Americans. There is no other better way. There is no other dream of moving to another land. You are born here into this situation and you have to figure out how to work through a system to become successful. You play with the cards given to you. Resources and services are limited, different kinds of school equate to different opportunities. The reality is that “hope” is already here and you have to pursue it in unconventional ways, because conventional ways aren’t always equitable.

Journalist Juan Gonzalez was born in Puerto Rico and raised in East Harlem and Brooklyn. He attended Columbia University, joined the movement against the Vietnam War and helped found the New York City branch of the Young Lords in 1969 as the minister of education. He has worked as a columnist for the New York Daily News for many years and knows the Nuyorican community deeply.

Asked what pa’lante means today to young people, Gonzalez said, “Things have dramatically changed since 1969, but the idea of pa’lante is the same. You gotta keep struggling and keep going forward. You can’t go back. Whatever the situation is, and no matter how bad the economy gets in Puerto Rico, or the challenges young people face getting work, you can’t go back.“ For young Puerto Ricans the chance of success hasn’t changed, but the hustle mentality continues to evolve and grow.

After all, Puerto Ricans have endured decades of generational poverty. They survived the collapse of the island’s sugar cane industry and the depression that followed in the 1930s and 40s. By 1950, more than 250,000 Puerto Ricans lived in New York. By 1970, the number was nearly 900,000 according to U.S. Census figures.

Many had rights as American citizens. Yet, they encountered poverty, poor education and unemployment. They lived through the years of the burning Bronx and continued to fight.

But generation after generation of poverty in the “land of opportunity” has worn away at the outlook of Puerto Rican youth and their hopes in what they can do with the limited resources available.

Sitting across from me in a graffiti-decorated bedroom in the South Bronx was the epitome of the underdog resilience to defy stereotypes.

Hip-hop artist Chief 69 didn’t go to college, yet he managed to successfully create his own business offering services like rapping, graffiti art and breakdancing at schools and in the community. The 24-year-old’s story was recently featured in the New York Times.

“I don’t want to work a regular 9 to 5 at some office or doing customer service and hating my job,” said Chief 69. He echoed sentiments that are common among people of his generation.

“You make your own way out. You make your own business or your own invention. Look at most people who are successful that are Americans. That’s just part of the American way.”

So why should we be paying attention to Puerto Rican millennials in New York?

Because often times their voices are not heard in the mainstream media.

A recent study shows that Puerto Ricans are faring worse than other minority groups with “lower rates of school enrollment, educational attainment, and alarmingly higher rates of disconnection and poverty than other native-born Latino youth,” according to the Community Service Society.

Since 2000, Puerto Rican migration to the U.S. has again surged as Puerto Rico’s population declines. The nearly 5.1 million Puerto Ricans in the United States now far outnumber the 3.5 million on the island. They are the second largest group of Latinos in the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center.

Puerto Rico now holds a debt of $72 billion that Governor Alejandro Padilla said the commonwealth cannot pay without help. Absent that, the local government will not have a choice but to further cut back resources on necessities like hospitals, police departments, public education, and public transportation. All of which would push people out faster and plunge the economy down faster.

But there is some hope.

On a warm day at the Caribe Hilton in Puerto Rico, hundreds of young faces, charged and determined, shared a variety of innovative ideas and attended talks by tech entrepreneurs from different parts of world. The H3 conference, meaning Hipsters, Hustlers and Hackers, was on its second successful year bringing together designers, investors and developers to create local businesses and export globally.

One millennial, Pedro Cruz, 21, whizzed around showing potential investors an app for virtual real estate tours called Touralo. Another, Maria-Laura Martinez, 25, won design awards in London for jewelry created using 3D printing techniques. A group of college students won free tickets to the conference because of their idea for an app that saves people time waiting at the doctor’s office.

Conferences like H3 aren’t the only ones supporting the momentum for the innovative startup scene on the island. Organizations like Piloto 151 in San Juan provide a co-working space, while Codetrotters serves as an intense academy to train software developers.

Within the fabric of a fleeing population, people want to stay and build the future of the island. Isabel Rullan, 27, co-founded ConPRmetidos, a startup linking Puerto Rican professionals in the diaspora with the mission of investing and building on the island.

“As citizens we have a responsibility to also do something for the island. We went to college and we are prepared,” she said. “We can create a movement, we should step up to the plate.”

Photographer’s Note

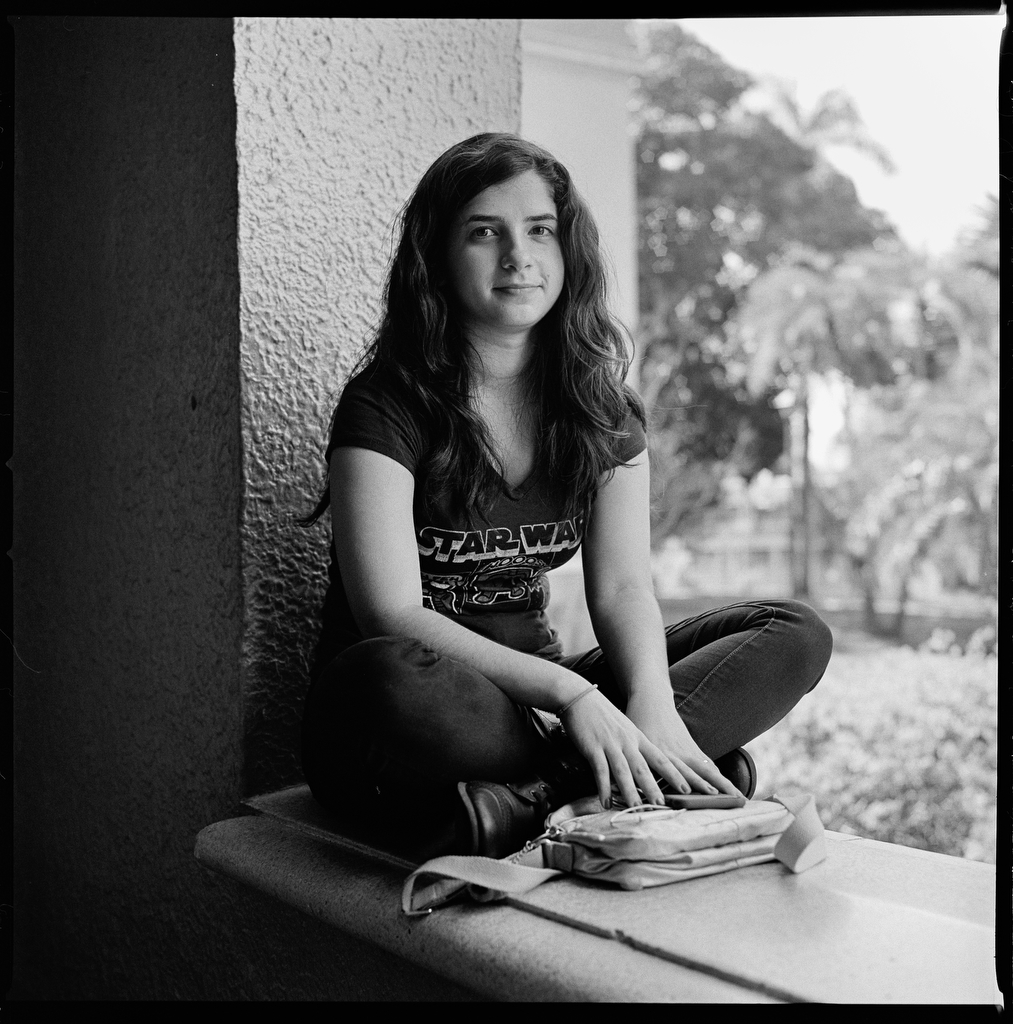

These portraiture series explores the perspectives of young Puerto Rican pursuits in a variety of different fields — both in the Bronx and in Puerto Rico.

The Bronx images range from leaders that I know in my immediate community to people I met on the street. The hustle mentality in the present day, something people can learn from. They teach us about the hope of people born without privilege who are willing to fight for a chance at a better life.

The Puerto Rico images are the faces of island-born millennials: entrepreneurs, students, cooks, designers and hackers. During this assignment I made an effort cover as many different stories as possible. There are many more to be told. Time was limiting, as well as the tools and technique I used for this project.

I worked with a 30-year-old Hasselblad film camera, only 12 pictures per roll, and hand developed the film in the basement of the Bronx Documentary Center. This antiquated process allowed me work slow and think carefully on how to best tell their stories in a formal portrait series. I drew on inspiration from photographers like August Sanders and Walker Evans whose work has shown me the strong documentarian purpose of portraiture.

Growing up in the Hunts Point section of the South Bronx, I was one of the many young Puerto Rican faces in New York City trying to make it. My family came to the mainland in the 1980s, Dad worked blue collar jobs while my Mom worked as a gym teacher. Back then the Bronx was still burning and the streets were up in arms. But we were safe. I was the youngest of three and my mother worked hard to keep me off the streets.

My brother alone went through enough street brawls to teach me right from wrong. I am here today as a journalist and photographer with the privilege to tell the story of my community thanks to my mother who made financial sacrifices for a quality education so that I can Echar Pa’lante!

![Felix Rodriguez DeJesus, 21, is studying Architecture at the Pontifical Catholic University in Puerto Rico and is the founder of ReSight, a sunglass company using reclaimed wood. "I always had the plan to have my own businesses," he says. "But I never thought in my mind that it would be so [early]." (Edwin Torres/GroundTruth)](https://d3oj2y7irryo5z.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Puerto-Rico01.jpeg)

![Maria Laura Martinez, 25, in partnership with Vincente Gascow founded Keznr Jewelry, utilizing 3D printing and design. Her latest collection won three design awards in London. "People think [because] you're Puerto Rican, you're not legit or believable," she says. "The jewelry started moving when I won a prize in London. It required a validation for people to see it here on the island and that it was worth it." (Edwin Torres/GroundTruth)](https://d3oj2y7irryo5z.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Puerto-Rico08.jpeg)