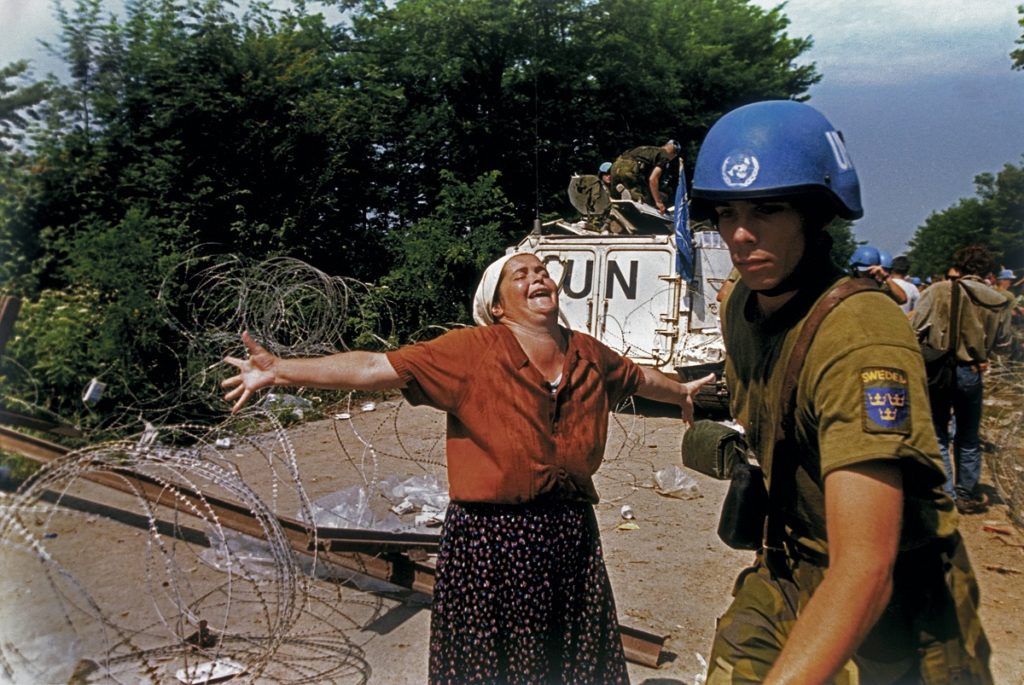

Peace is not simply the absence of war. It is a complex and often-fragile condition that requires courage and careful tending. Peace is often unsuccessful, as countries slide back into war. The new book, Imagine: Reflections on Peace, created by the VII Foundation makes a deeply compelling exploration of these and other topics in the intersection of war and peace.

Contributing to the book are photojournalists, diplomats, peace negotiators, combatants and survivors: the result is a complex tapestry of peoples’ experiences with creating and maintaining peace from the wreckage of war.

Although this book is more than a decade in the making, Imagine could not have arrived at a more relevant time. In the aftermath of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris’ victory in the 2020 election, talk of violence, insurrection, and civil war has reached a fever pitch among Donald Trump’s most fervent supporters. Violence against the media has ramped up, with several journalists assaulted and threatened over the last weeks. Constellations of violent ideologues have coalesced around the idea that a civil war could be on the horizon. Antiracist and antifascist groups have made it clear that violence from the right will not go unanswered.

In his first address as president-elect, Biden spoke of the need to “lower the temperature of our public dialogue.” Of course, the most incendiary dialogue comes not only from our political leaders’ public statements, but from regular people who see the “other side” as their enemy. Calling for “peace” is just another shout amidst the cacophony right now.

The renowned photojournalist and one of Imagine’s principal architects Gary Knight said the impetus for the book sprang from his own dissatisfaction with where a career photographing war had left him.

“I had just come back from Iraq and was just done with photographing violence,” Knight said. “My work was not used consistently with my motivation for going to war – I didn’t want to glamorize war but often my pictures were presented that way. I was just exhausted and thinking about how difficult it would be to make peace in Iraq. And then I started thinking about the other wars I’ve covered and wondering how successful peace has been in those places.”

The book is organized into case studies of countries that have been through war and have created peace, with varying levels of success. Each case study has photographs from “then” and now, as well as narrative essays written by people who lived through the conflict, the reconciliation process, or both. The peace processes in Lebanon, Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Northern Ireland, Colombia, Iraq and Syria all have important lessons for the U.S., and the world today.

Knight came of age photographing the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia with Roland Neveu, and both of their pictures are presented together to introduce the “then” of that war. The fist picture, by Neveu, is of a young Cambodian government soldier wildly firing an obsolete rifle at Khmer Rouge troops, a record player and records scattered around him in his foxhole. This is not a book about how war is terrible and peace is very nice – that’s a pretty low bar to hurdle. This book is about peoples’ experiences with peace, which are as often experiences of prosperity as they are of suffering and injustice. To that end, when Knight returned to Cambodia to photograph the “now” chapter, he talked to a wide variety of people who lived the war, and made quiet, formal black-and-white portraits of them. The genocidal Khmer Rouge regime was famous for making portraits of prisoners before they were executed, and Knight’s visual approach references and reconciles with this cruel history. Seeing his evolution as a photographer through this book is a peace process in itself.

In Lebanon, the “now” photo essay is by Nichole Sobecki, who initially went to Lebanon on a university research trip, and stayed on as an intern at The Daily Star. While researching the political complexities of a post-conflict society for her studies, she was also publishing her first pictures and occasionally writing horoscopes.

“I didn’t go to Lebanon with the intention of covering conflict,” Sobecki said. “On the morning of my 21st birthday, fighting between the Islamic militant organization Fatah al-Islam and the Lebanese army broke out. I covered the story, and for the first time saw war. So yes, Lebanon was a defining place to begin my career. It taught me less about conflict specifically though, and more about how war and peace exist in a continuum — and that our fates are decided in the space between them.”

For the book, she decided to spend time with Hamza Akel Hamieh, the former commander of a Shia militia who hijacked six planes between 1979 and 1982 in order to bring attention to the kidnapping of his religious leader Musa Sadr. While Hamza believes the peace in Lebanon is fragile, Sobecki shows him playing with his grandson and revisiting memories with his family.

“Hamza was an old friend of Robin (Wright’s), so I was fortunate enough to walk into a space of trust that had been built over decades,” Sobecki said. “Unknowingly we arrived at his doorstep on Hamza’s birthday, and ended up being welcomed to share a beautiful lunch with the whole family on their porch looking out across the hills and farms of the Bekaa Valley. We didn’t realize it at the time, but this would be his last birthday. Afterward, I had the chance to just see him with his children and grandchildren — the man behind the famous hijacker — and to learn about what had prompted his actions as we flipped through old photographs and memories.”

Other pictures show the scars of war still evident in Beirut – memorials, museums, and shell-pocked exhibit spaces. Clearly the path to peace is not to bury the past, but to reconcile with it.

“What I’m most drawn to cover though are the quieter, more complicated realities that bookend war, said Sobecki. “What overlooked political and social currents flow through a region long before arms are gathered? How do questions of justice, forgiveness and memory contribute to a lasting peace?”

Like previous books from VII Foundation and the contributing authors, this book is destined to get a lot of attention at the scholarly, policy-making and diplomatic areas of discourse. However, I found the book to offer a tremendous amount to the more casual reader like myself, the student of history, the photography enthusiast, the citizen concerned about the deep rifts in American society. The book’s design and production helps make it accessible – Imagine is printed in France on a beautiful uncoated paper that is shockingly lightweight. The sewn binding opens flat, making it easy to read in one hand. Imagine is not a glossy anvil that will live on the coffee table – this is a book to throw in your backpack and lend to your friends.

Related: A lens on war frames an understanding of peace