This column originally appeared in Navigator, GroundTruth’s newsletter for early-career journalists.

For this edition of Navigator, we invited Ben Brody, GroundTruth’s director of photography, to talk about his experience and dedication to the craft, and ask what advice he’d share with emerging photographers and those journalists for whom photography might not be their first medium, but who find themselves taking pictures in the field. Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Report for America welcomed its new class of corps members into service during one of the most transformative and singular periods in living memory. Much of their first weeks on the job have been spent covering protests while adapting to a new newsroom and, in many cases, an unfamiliar part of the United States.

Among the 10 new corps members focused specifically on photography, the conversation has delved deeply into navigating our role as journalists in this moment. I am encouraged to see that early-career journalists are rightly skeptical of the idea that photojournalism is a benignly benevolent practice, and recognize its troubled history of marginalizing indigenous and disenfranchised communities, even justifying violence against them.

GroundTruth and Report for America’s mission is steeped in a solutions-based approach to storytelling, and that extends to our own journalistic practice. In the quest to always do better and tell stories more effectively, we have to scrutinize our own practices. I started my career in photography making propaganda for the U.S. military in Iraq. The next 17 years of photographing war and the U.S. military in an increasingly independent and analytical manner led me to publish the photobook Attention Servicemember last year, where I reckon with my role in the wars and photography’s role in culture, society, and what we perceive to be true.

Selin Thomas: What makes a good photo?

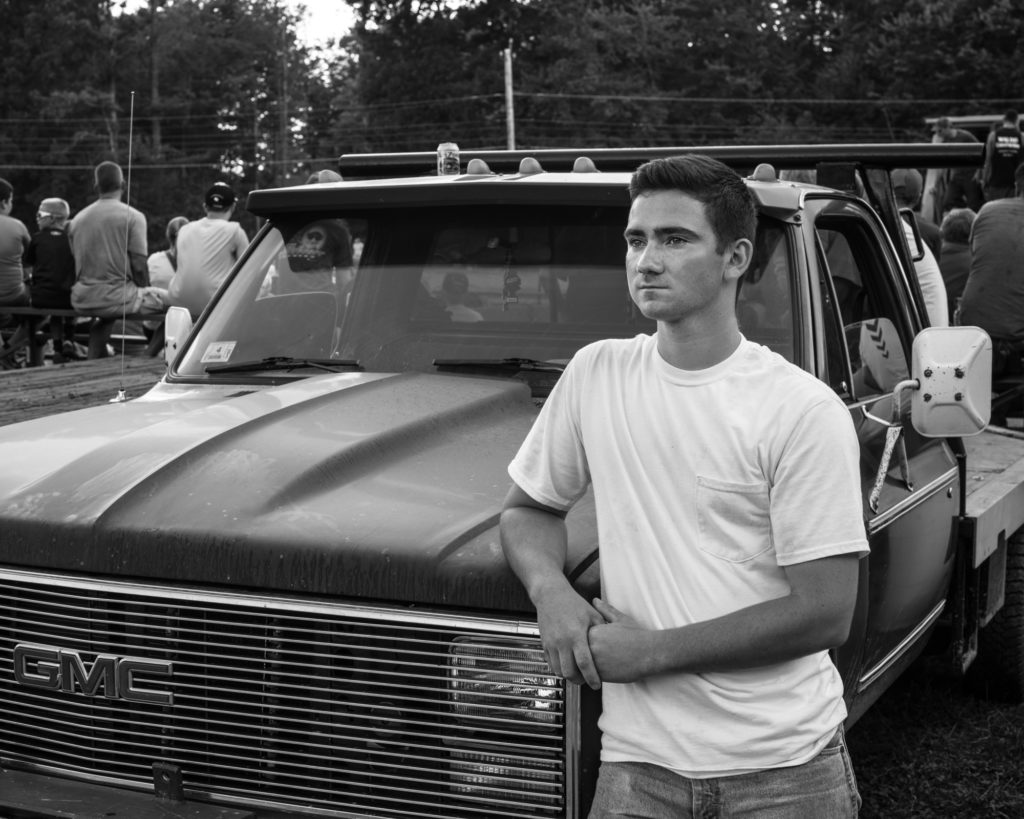

Ben Brody: As a writer, you know the important writers, those who are influencing you. What are the things you’re reacting to in a literary sense? What are you adding to their press release as a journalist? It’s that kind of literary color you can put into your photography. You’re there to create an atmosphere. The boy at the back of the school board meeting eating an ice cream sandwich–that’s the mood of the room. Photographing the mundane is a really exciting theme in photography. There are a lot of photographers who work with it specifically (Stephen Shore; Joel Meyerowitz). You have to give people a point of entry.

ST: How does one tell a story through photos?

BB: If somebody wants to become a better photographer, the most important thing to do is look at a lot of photography. You have to look at photos, at what you’re responding to and really try to figure out why that is.

What in the power of description are you really responding to? How does it advance the story in a gripping way? How does it affect the way you see the world? Photography is kind of magic in that things reveal themselves, and communicate more than I can otherwise. It was the way I could communicate something real, and my audience would see themselves reflected in the work I did, the people in the stories I was telling could feel it was authentically told. Photos that are authentic to the people in them.

ST: What was your introduction to photography?

BB: Like a lot of photographers, I got interested in the gear aspect of it. As a teenager, it was an expensive, finicky object that you can use for your own purposes. In high school, (mid-90s) I took an Intro to Photo class.

I discovered if I took photographs of sports for the yearbook, I didn’t have to play them. It was something I found intellectually challenging and really physical. It engaged me on a lot of levels and it was clear to me almost immediately that what I wanted to do was take pictures.

What I wanted to take pictures of has changed over time. I’ve been exploring a few of them over the last 25 years.

ST: What was the first thing you learned as a combat photographer, and how did it inform your work?

BB: I joined the army in the run up to the Iraq war. I felt it was my generation’s Vietnam. I knew I wanted to photograph it; I had to be there, I had to see it. Being a Jew from Eastern Mass, I was deeply skeptical but I felt an essential step to adulthood was taking a risk like this. I didn’t have any money or experience in photojournalism.

The first thing I learned on the ground in Iraq is wear your throat protector. These little pieces of metal fly around all the time. I have a few in my back. I learned that really quickly when a soldier I was traveling with had his throat cut which could’ve been prevented by a tiny piece of kevlar.

Starting with small format digital cameras in an emotionally intense, physically intense environment threw me for a loop. I took the best pictures I could. You have to point the camera at something, you have to push the button. I followed the instincts of what was interesting but the functionality of my pictures–what my editors wanted–was for me to take the photos in a really specific way. My ‘editor’ was a sergeant first class, big, burly; you may have a different relationship with your [editor].

The pictures from my first tour are really interesting even though technically really weak. Photographing soldiers dressing up, taking talent shows, legs sticking out of humvee doors, selfies in the mirror, being more playful with the camera. That, in retrospect, created a more real, effective version of the war than the sanitized ones.

So the advice I always give is don’t worry so much about what your editor wants to see. Your editor has experience that you can’t figure out. And that can lead to self-censorship. Yes, you want to vary distance, a good mix of horizontals and verticals, but that’s not to give your editor a picture that will fit in a specific text space. That’s so when you put the photos together, you can make a rhythm and flow in the imagery. You can lead people in and you can lead people out. Send as many photos that the editor is willing to look at.

ST: The arc of a photo narrative is like all storytelling. How is it also different?

BB: There is a lot of utility in looking at it and thinking about how to construct a story when it comes to taking pictures. Photography has to be made in real time, in interaction with the world. You can’t be a fly on the wall as a photographer; the act of taking photos is necessarily intrusive. You will affect the situation. Sort of like juggling chainsaws. You can always push yourself further, you can always do something with photography.

ST: How do you ensure your subject’s dignity in fraught situations?

BB: Photographing people who have been wounded or are in extreme pain is really difficult. Sometimes they want to be photographed to communicate their pain to the world, as a symbol to represent this great wrong. Even if you convince yourself that’s what you’re doing, there’s a cost to you and the person being photographed.

The fly on the wall is false to journalism, the sooner you get that into your head the better. Coming from the field of war photography, something I have to and do think about a lot is whether the work I and my colleagues made had any effect on the war. The only pictures that function that way from the Iraq and Afghan wars are those from Abu Ghraib. The reason the non-photographic audience reacted to those pictures so intensely was because they weren’t by someone trying to make an image. They were by people who were knowingly complicit, actively part of this situation, bringing the audience into the photos in a way that did have the impact: what people who look like them are capable of.

A camera merely describes where light affects a surface. The reason your photography is never unbiased is because you make decisions about where you point the camera and when you push the button. It can give agency to your subject, dignity to your subject, or it can take it. Khalood Eid’s recent NYTimes work of victims of child pornography is an example. A hooded or deep shadow lends a sinister aspect, and instead of that expectation, the women she photographed for the cover were two strong, vibrant women. How could she photograph them in a way that empowered them but didn’t show their face? They’re in a structural embrace, on a bright, sunny day. The light is gorgeous, explanatory, it doesn’t hide anything; it shows the strength and power of their bodies. I felt that was an amazing example of how to approach a difficult photographic situation.

Putting the distance between you and the subject isolates the subject, it’s a dangerous approach to showing someone’s resilience in a difficult circumstance and it isn’t going to fool the viewer. A 35mm or 50mm lens, which approximates the perspective you see normally, is the first thing you can do to avoid the colonialism of photojournalism. It forces you to get close, to be intimate with your subject, which communicates to the viewer who they are. Immerse yourself in religious iconography. Or painting. Elizabeth Hermann’s photos of 131 women of Congress is another great example.

ST: What is the greatest need in photojournalism today? Why?

BB: The needs of the moment change. Your ability to communicate to your audience changes as the reactions to things change. That sort of fluidity is really important right now. It’s not having a style. That stuff catches on very briefly, nothing you want to make a career out of. But when you come up with a visual approach with a visual concept that serves your subject well, that transcends time, style and the news of the moment, if your work happens to be of a subject that is of general interest, people will really notice. There’s so much photography of the daily grind nature that doesn’t really inform us. As a career photographer, the goal is not only being successful but creating something that can continue to inspire, generate you. Never get lazy, think about how you can push further, see deeper.

Getting people together to look at pictures, at public art, getting people to look at photos in public spaces can have a tangible impact. You want the viewer’s reaction to be thinking more about the story. Print is a great way of slowing people down. If online is your medium, you have to think about what you’re really getting, what is your opportunity to communicate.

ST: Do you have any mantras that you carry around?

BB: “Good food is really about giving a shit, isn’t it” –Tony Bourdain. And I have Diet Coke first thing in the morning.

ST: Do you take photos on your iphone? How do you adjust your form?

BB: It’s a brutal life. You have to really want that, to communicate at that level. People respond to the sacrifices people make to get the photo. That is part of engaging the viewer.

But really simple projects are really fun too. You can make typologies, like every ice cream stand in the county, photographed all the same way, present them in a row, nothing making them complex, really stupid but also awesome. These dumb ideas can be really cool and magical, especially if you present them in a way that you can control how they’re seen. Like printing them and stacking them at the local coffee shop, places that are familiar to people but that they haven’t seen in this way before.

The barrier to entry has never been lower. Communicating with your community, establishing yourself as someone who makes tangible, durable objects, challenging yourself to learn more about how pictures function, and how people react to them. I love making prints for people. It’s so easy to do, people really respond to it.

ST: How do you learn to trust your visual instincts?

BB: It’s hard and you’re going to make mistakes. It’s an important thing for journalists to understand that they’re doing their honest best to understand what’s happening and communicate it in a good faith way. It’s not fair for people to think of journalists as omniscient. If you take that burden off yourself and do your best to expose yourself to perspectives that you might not hold personally you can make effective journalism that will communicate to people. It’s difficult with the hostility people are showing to journalists. You just have to present yourself as well as possible, demystify the process.

ST: Whose work should we be looking at?

BB: The work that speaks to you.