This column originally appeared in Navigator, GroundTruth’s newsletter for early-career journalists. You can subscribe to Navigator here.

The perks of being a music journalist make it one of the best gigs in the industry — free concerts, free music, the chance to meet celebrities — but the beat is also one of the most misunderstood.

Writing about music goes deeper than an impression of a concert or album — music opens a window into the zeitgeist of our times and times past. Songs offer up a chance to discuss hot-button issues packaged in a medium that can transcend the political, cultural and social controversies of the moment.

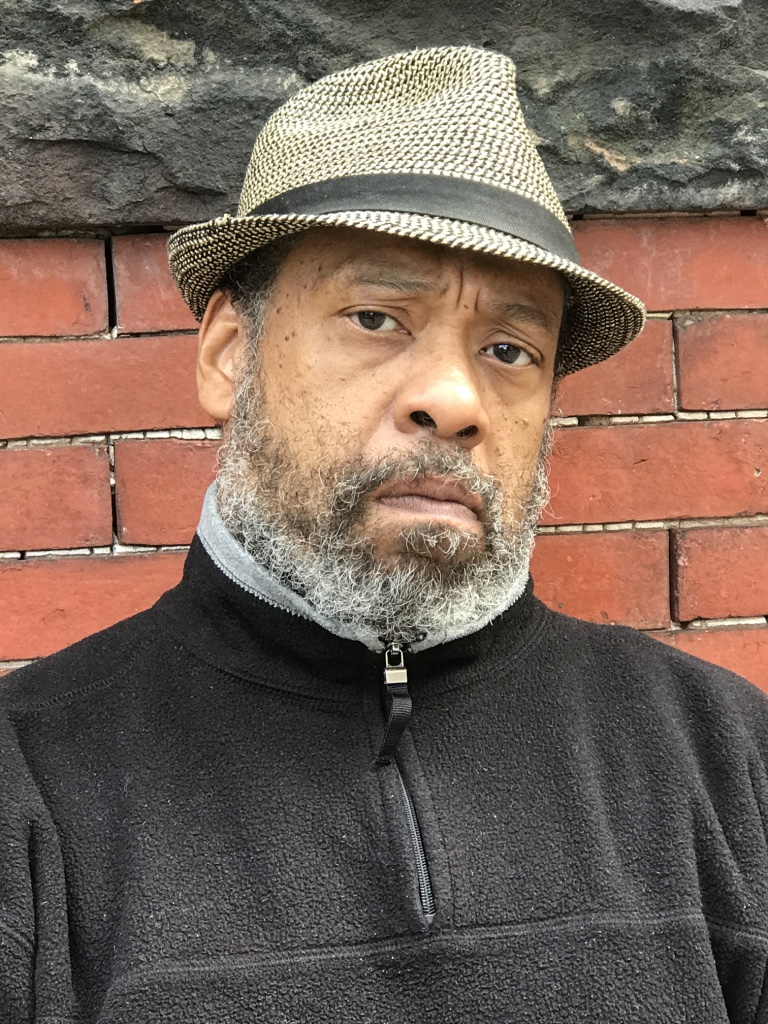

To understand what journalists need to know if they want to follow this career path, we spoke with Michael A. Gonzales, who wrote about hip hop for pioneering “urban” magazines such as The Source, Vibe and Ego Trip, during a time when mainstream music journalism disregarded the genre.

Gonzales recently reflected on his career in a Longreads essay, which traced his evolution as a music journalist alongside the rise of hip hop — from his childhood in mid-’70s New York City to his success as a writer and critic profiling icons like Jay-Z.

We asked Gonzales what lessons he learned at different stages of his career, from interviewing his first music legend (Barry White) to writing cover stories for The Source to crafting cultural criticism for the Paris Review. His answers were edited for length and clarity.

Side A

1. Expand your music diet

“If you’re a music writer, you need to open yourself up to other kinds of music that aren’t necessarily what you like,” said Gonzales, “because you can learn so much.”

In the context of hip hop, for example, samples of other artists’ music are an essential, often intentionally referential aspect of the artistic process and the new song that results.

“If you’re writing about a song that samples a Billy Squier drum beat, for instance, you could obviously write the story without knowing about that sample,” he said. “But I like stories that are more than that — for me, the details make the story richer.”

The beat that drops during the initial, eponymous refrain of “Girl on Fire” by Alicia Keys, for example, is a bite from ‘80s rocker Billy Squier’s song “The Big Beat.” Otherwise obscure, that same, big beat can be recognized on a number of other hip-hop tracks.

Gonzales recommends taking a tour through all genres. “I mean, I even went through a phase when I was listening to old country,” he said. He continues to listen to big band standards by George Gershwin and Duke Ellington.

“I think a lot of times writers get bogged down by genre,” says Gonzales. “People are like, ‘Oh, I’m a rock writer, or I’m a hip-hop writer, and they don’t explore beyond those boundaries.’”

2. And while you’re at it… READ

“To me, the biggest mistake a lot of young writers make is that they don’t read enough,” said Gonzales. “People need to read more history, especially if you’re writing about music, buy some books about the Brill Building, buy some books about jazz from the ‘50s, the Bebop era — like, you need to know this stuff!”

Though he did learn a bit of guitar as a kid, his education in music writing was a self-driven literary pursuit. Growing up reading New Journalists like Tom Wolfe in the local library and reviews by Village Voice and Rolling Stone music journalists at home, he discovered a love for intellectual, genre-busting cultural criticism.

“None of these guys wrote about the music from a musicologist’s point of view,” Gonzales said. “They wrote more from a sociological point of view,” — what he calls a sometimes emotional, more often intellectual perspective — “and I felt like I could do that.”

3. Do your research (it’s easier than ever!)

Whether you’re profiling an emerging artist or a high-profile, multiplatinum band, there is background research to be done.

“I think a lot of writers sometimes are lazy, in terms of doing their research,” Gonzales said, “even though now everything is at your fingertips.”

These days he does much of his research utilizing vast digital archives like Google Books. Though he cautions that some material seems to be disappearing from the Google database, he says it’s still a wonderful, free resource as a music and pop culture writer.

“Because I write a lot about black culture and black artists and black writers, I’m finding old magazines like Ebony or Negro Digest, which later became Black World, a literary magazine,” he said. “So if I’m looking for an essay about Richard Wright, I can find all this stuff in full on Google Books — it’s become one of my main resources.”

Despite its paywall, Gonzales also highly recommends Rocksbackpages.com for professional music writers: “If you get a subscription, you’ll probably be on there for 48 hours.” Created by music journalists for music journalists, Gonzales says a lot of the material in the archive can’t be found anywhere else.

“Recently, I decided I wanted to write a story about Thin Lizzy,” he says. “I went on [Rock’s Back Pages], and I found all these articles about Thin Lizzy, all these interviews were still living, that were published in the ‘70s.”

Side B

Now that you have the basics, here’s how you nail interviews with music legends

4. Interview the person, not the persona

As Gonzales describes in his Longreads essay, he was “nervous as hell” to fly to Europe and profile the “Walrus of Love,” Barry White in ‘95. This was Gonzales’ first high-profile interview and he had to break through White’s “tough persona.”

So how did he prepare? By showing White that he was interested in him as a person, Gonzales was able to get him to open up, eventually coaxing out White’s recollection of collaborating with Marvin Gaye.

One of his main critiques of celebrity interviewers is that their story begins whenever the person became famous.

This can easily end with the journalist becoming the persona’s plaything, as was the case for an unlucky Time reporter who did not seem overly prepared for an interview with Bob Dylan.

“People respect you when they know that you know what you’re talking about,” he said.

The interview with White was pre-internet, so Gonzales found as many articles as he could about the three-time Grammy–winner at the library, looked up albums that he worked on, and — most importantly — tried to find out stuff about his life before fame.

Gonzales likes to ask people about where they grew up. He suggests these questions:

- Do you remember the first record you bought?

- Do you remember the name of the record store?

- Do you remember the name of the English teacher that first told you that you were a good writer?

“I need to know who you are before you step foot into the studio,” he said. “What forms you as an artist, as a singer, as a writer, as a musician?”

5. Don’t ask the question and give the answer

If it’s already hard enough to get a source to sit with you for more than 15 minutes, don’t fill that precious face-to-face time with comments or hyper-extended questions.

“Let your subject talk for themselves,” Gonzales said. “Don’t try to ask the question and the answer.” Yes, write down all those questions you want to come up during the course of the interview, but, also, be sure to shut up and let the subject do the talking.

“When I listen to some of my early interviews, I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I wish I could shut the hell up,’” he said. “Like, I’m trying to interview Curtis Mayfield, and I’m talking and talking and I’m thinking, ‘I should not be listening to myself talk on this tape that much.’”

“I think sometimes it’s nerves with younger writers or we want the subject to see how smart we are, and how much we know about their stuff,” he says.

6. Don’t try to perform for your interviewee

“I’m not sure if this is worse with people that write about hip hop or if this happens with rock journalists too,” said Gonzales. “But I’ve heard horror stories.”

He recalls what the rapper Nas told him after a couple days of following him around for a story.

Gonzales said that Nas praised him for being different than most writers. “He told me, ‘I always find these [writers] want to, like, rap for me.'”

There’s a pervasive stereotype of music journalists being failed musicians or failed rappers, Gonzales said, and that shouldn’t be the root of a music journalist’s calling.

“I’ve always wanted to be a writer and I think the one thing that kind of separated my thinking from a lot of other people’s was that I never thought I was in the music business […] If I wrote about music, then it was a blessing.”