It wasn’t until her first computer science course at Harvard University that Anne Madoff began to realize how few women work in technology.

Madoff, 23, started taking programming courses in high school, where she was one of the few girls in her class. She only realized later that women occupy just 25 percent of the professional computing jobs nationwide. The number is below 20 percent at Google, Facebook and Twitter.

“I think I had that clichéd millennial mindset that the glass ceiling was broken and that gender was no longer an obstacle,” Madoff said. “It’s not something I really thought of at all in high school.”

College was different. Entering Harvard with computer science experience, Madoff started off in a more advanced course, where she started to feel self-conscious in a way that she simply hadn’t before.

“The most specific difference I can describe is that if I said something stupid or asked a naive question, I felt that I would be reflecting poorly on women,” Madoff said. “I felt that I was this representative and that my failures also reflected upon on my cohort.”

She now works as a software engineer for Mark43 in New York, a startup that built a cloud-based platform designed for law enforcement agencies.

Dabbling in computer sciences during high school certainly isn’t common. Madoff is a special case, having walked into college with basic programming experience. For her, it paid off.

“I’m someone who really benefitted from starting young,” she said. “The biggest thing that doesn’t get talked about is the efficacy of early intervention. We all think it’s a good idea to code early.”

Making sure that there’s a solid school-to-workforce pipeline for women is essential, according to Deloitte Global, a consulting firm.

Deloitte predicted that less than a quarter of all IT jobs in developed countries will be held by women by the end of 2016. The projected numbers would be the same as last year’s, or perhaps even lower, depending on the source.

It might be a result of the drop off among women and girls as they get closer to entering the industry. According to Girls Who Code, a nonprofit that aims to close the gender gap in computer science, 66 percent of girls aged 6 to 12 show interest in computing programs. By the time they reach college, that number drops to just 4 percent.

Margo Seltzer, a computer science professor at Harvard, says that the low retention rate among women and girls is just as important as the “pipeline problem.”

“I’m getting tired of people in the industry writing it off as pipeline problems,” she said. “The retention problem is real and the recruiting bias is real. I don’t disagree with [the pipeline problem] at all, but that does not excuse the industry from actually understanding this issue and dealing with it.”

According to a 2014 study from the Center for Talent Innovation, women in IT roles are 45 percent more likely to leave in their first year than men are.

Seltzer attributes it to implicit gender bias.

“For most people, it’s not the overt, horrible sexism,” Seltzer said. “It’s the steady drip of the undercurrent of implicit bias – harmless things such as referring to programmers as ‘he’ … Fatigue from feeling that you don’t always belong.”

Amy Yin, a former classmate of Madoff’s, says that she was put off by the brogrammer culture of her first workplace out of college. She now works as a software engineer at Hired, Inc.

“I felt all the offsite events were testosterone-filled,” she said. “Anyone can go to a shooting range or whatever, but it’s not necessarily fun for both parties.”

Madoff remembers when she interned as a software engineer for three summers in college. She says that many people didn’t expect or believe that she, a woman, could hold such a position.

“It’s not necessarily any individual person being a jerk, but I have often worked in larger companies where people ask, ‘Oh wow, why do you have that up?’” she said, referring to when she was seen coding at her computer.

Another major issue for women is pregnancy, since it affects the amount of time that they can spend working.

“It’s a really public thing for a women, and a really private thing for a guy,” Seltzer said. “This is a really complex issue. Not just the fact that it’s the women giving birth.”

Many companies who boast about their progressive paternal leave policies arguably help men more than women, according to a recent New York Times article.

One woman in Yin’s social circle was explicitly advised not to get pregnant.

“My friend, who is at a major tech company, was told not to get pregnant – that getting pregnant is detrimental to your career,” she said.

Men who take parental leave often can use this time off to work on research or their own startups, while women are more likely to focus on childrearing.

While numbers for women in tech remain low, Deloitte’s projection included some positive changes – more women are holding senior positions in tech now than ever before.

Jodi Goldstein held a number of senior positions at tech startups and now serves as the managing director for the Harvard Innovation Lab. She says that women should push harder to show their abilities, although it can be difficult – on several occasions, Goldstein was discouraged from others in the industry because she stood out as a woman.

“That’s the kind of world we live in, so we can’t cry about it. I just want to be good at my job and be appreciated for that,” she said. “I’ve always felt very strongly that I don’t want special treatment because I’m a woman.”

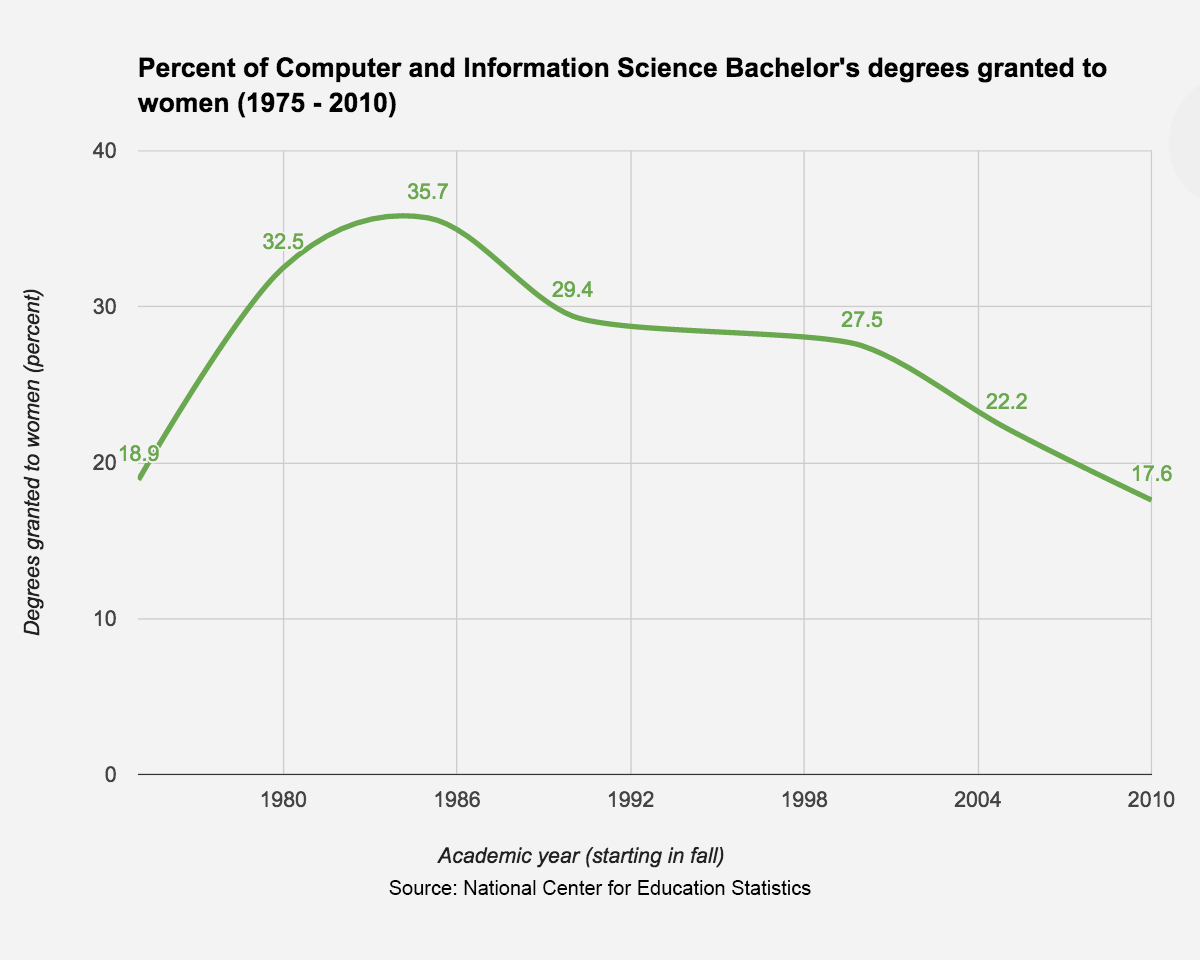

Many are hopeful that the tech industry’s gender gap will further close in 2017, as more people start to pay attention to it. Goldstein and Seltzer say that they’ve anecdotally seen more women enroll in computer science courses at their institutions, though some data suggests the opposite trend nationwide.

“I really strongly believe that we’re entering the year of the woman,” Yin said. “I really hope that we have stronger female role models so women will want to shoot higher.”