California:

Amid displacement, a historic church endures

SAN FRANCISCO — In a neighborhood that once boomed with black-owned venues and hotels, and hosted musical greats like Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, a struggle to survive is underway. African-American residents and business owners in the Fillmore District are trying to preserve this historically black neighborhood.

It probably sounds like a common story in San Francisco, as the tech industry fuels the most expensive rental market in the United States and an extraordinary concentration of wealth. But in the Fillmore District, known in the 1940s and ‘50s as the “Harlem of the West,” this upheaval goes back decades further and steeps the current debate in a bitter history.

“African-American ownership [of] stores and restaurants and hair salons and barbershops, shoe shine shops … you watched it all disappear,” said 76-year-old Alexander T. Williams, who has lived within walking distance of the Fillmore since 1965. “As a matter of fact, my last barbershop just closed … I’m not sure I’ll be able to find a new barbershop.”

One part of the Fillmore District may now be protected from these changes: Third Baptist Church, the predominantly black church where Williams has attended services since 1968, won protected status last month [Nov. 15], when Mayor Ed Lee signed legislation designating it as a landmark. The church is on the corner of McAllister and Pierce streets, just a couple blocks from San Francisco’s iconic row of houses known as the “Painted Ladies.”

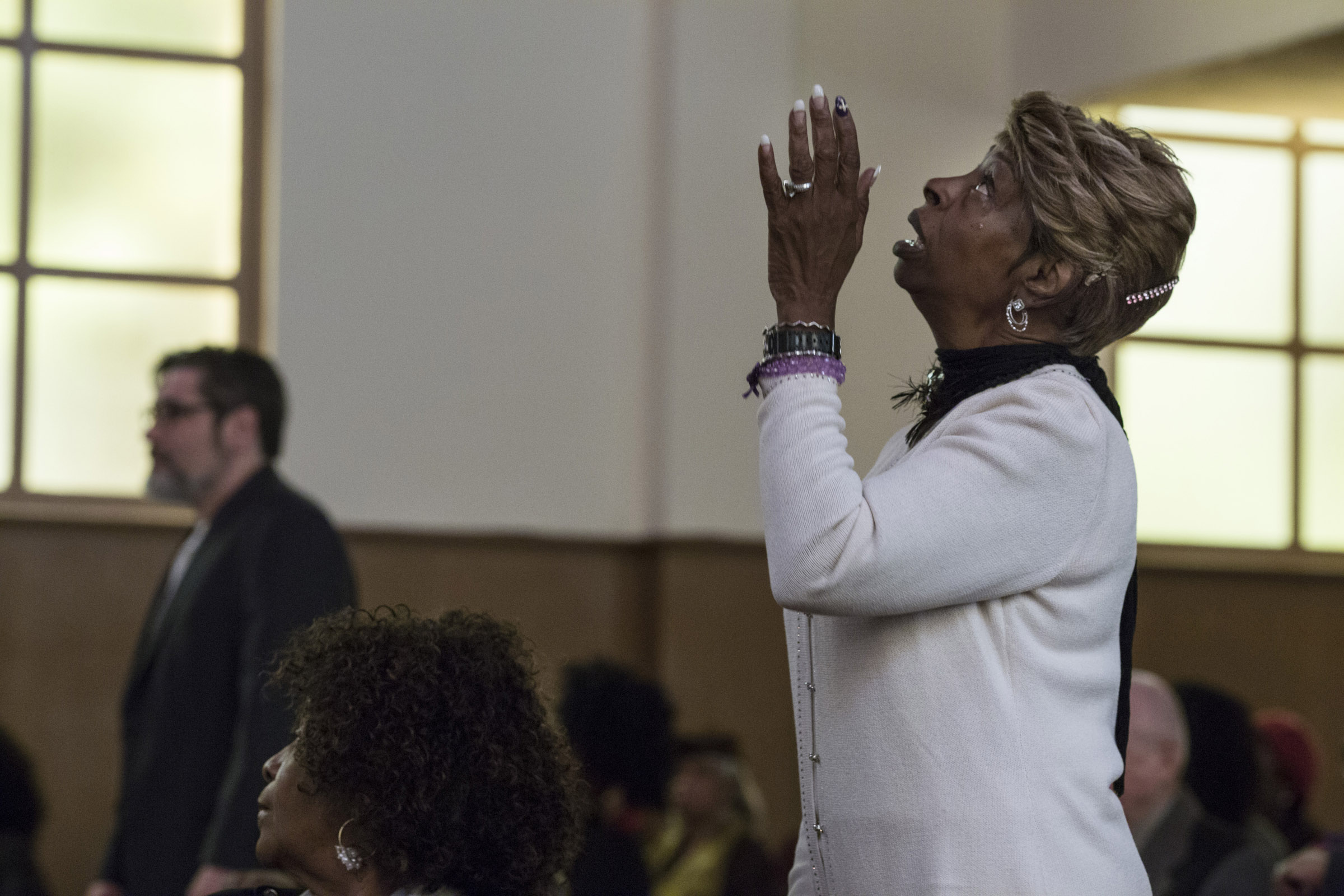

Williams calls the church “a beacon,” and recalls the days when there were no empty pews. “I joined in ’68. If you were not in this sanctuary by 11:30, there were chairs put down the center aisle and the crowd loft was completely full. This was every Sunday,” he said.

The landmark designation is a victory for the congregation, but saving the building is not synonymous with saving the church. Membership at Third Baptist Church has fallen from more than 2,000 to around 600, according to churchgoers, and the congregation continues to shrink, as people move out of the neighborhood. A couple hundred people attended services on a recent Sunday, with many trekking into the city from the East Bay and beyond.

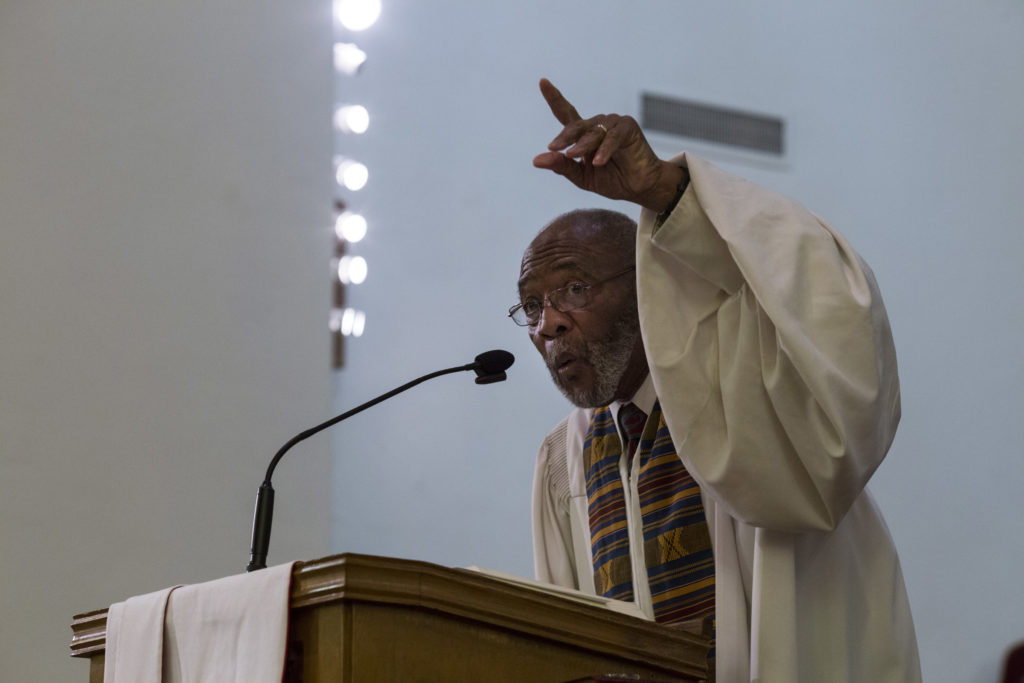

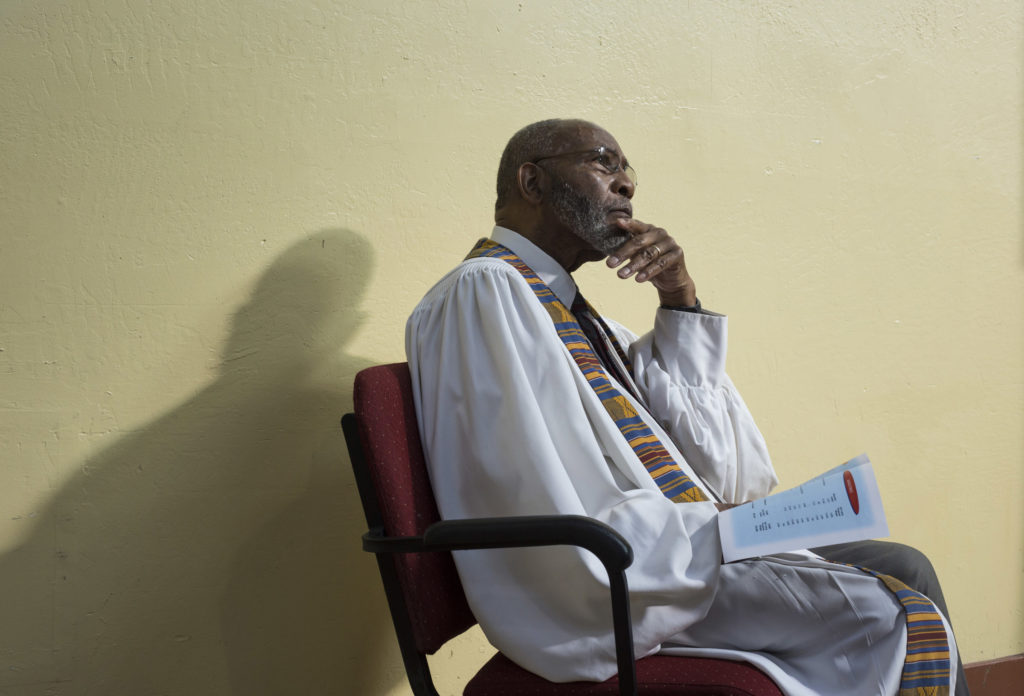

“Had not Third Baptist had its historicity, it would have been gone 10 years ago. It’s because of the respect, the loyalty and the appreciation for this institution that we have members as far away as Sacramento and Vallejo,” said Rev. Amos C. Brown, 76, who has been the pastor for four decades.

Founded in 1852 as the “First Colored Baptist Church,” Third Baptist was the first African-American Baptist church west of the Rockies.

“It began out of struggle, unlike an ordinary, regular church,” said Rev. Brown, who is also president of the San Francisco branch of the NAACP. “It was not just about personal salvation. It was about the salvation of the people. Third Baptist was founded in response to the racism in white First Baptist of San Francisco, which was founded in 1849.”

After moving several times around the city, Third Baptist Church found a home in the Fillmore District in 1952 — one hundred years after it was founded.

“Really, African-Americans didn’t come here for spiritual needs; they came here for social betterment,” Rev. Brown said.

“In a nonprofessional, strictly therapeutic way, the black faith community has always provided mental health, for it was in the church that there was their ability to gain a sense of somebodiness, of belonging.”

Throughout its history, Third Baptist Church played a role in civil rights and social justice, and Rev. Brown was well suited to carry on that legacy. Brown grew up in Jackson, Mississippi, and was 14 when Emmett Till — another 14-year-old African-American boy — was abducted and brutally killed for allegedly whistling at a white woman in 1955. Brown was so affected by the news that he reached out to civil rights activist Medgar Evers.

“Mr. Evers said to me, ‘Amos, don’t just be mad. Be smart,” Brown recalled. So Brown organized the first youth chapter of the NAACP in Mississippi. He became a Freedom Rider, and at Morehouse College, he was one of eight students in the only college class Martin Luther King, Jr., ever taught.

When Brown became pastor of Third Baptist Church in 1976, the Western Addition, which is the larger neighborhood that includes the Fillmore District, was undergoing rapid changes as part of a federal policy of “urban renewal.” Starting in the 1950s, the city used eminent domain to displace thousands of families, mostly African-American, to rebuild large portions of the neighborhood.

“They called it urban renewal; we call it urban removal,” said church member Alexander T. Williams.

Rev. Brown said it more plainly: “They had to find a scheme of public policy to get rid of us, and that was when redevelopment emerged, which was actually black removal.”

Census data shows the African-American population in San Francisco beginning to grow in the 1940s, when war-related jobs drew many from the South, and peaking in 1970 at 13 percent. From 1970 to 2010, the city’s African-American population dropped by half.

Church member Lois Carmack-Winder declined to give her age but said Third Baptist had not yet moved to its current location when she started attending at age 4 or 5, after her family moved to San Francisco from Louisiana.

“Now there’s nowhere else to move because we can’t afford it,” said Carmack-Winder, who now lives in East Bay, but commutes in every Sunday for church. “African-Americans can no longer live in San Francisco. Families with children can no longer live in the city. … We’ll be like the dinosaur. We’re going to become extinct.”

Nowadays, the forces working against the Fillmore District’s longtime residents are the same seen across San Francisco, now the most expensive rental market in the United States. The median rent for a one-bedroom unit is $3,390, according to a recent report by the rental site Zumper. San Francisco saw the biggest increase in income inequality of any U.S. city from 2010 to 2015.

“San Francisco is not the city of love anymore,” said Paulet Gaines, a salon owner in the Fillmore District who plans to close up shop. “The demographics has changed. It’s no longer African-American or black-owned businesses, black-owned residing.”

Gaines says she lived in the neighborhood 13 years ago. At that time, her rent was $800 a month. That apartment now rents for $5,000 a month, which is still well under-market, she said. Her father’s apartment nearby saw a more dramatic jump. When he died in 2016, he had been paying $872. Two weeks later, the apartment was rented out at $10,500 a month, she said. “No new amenities, no parking, no anything.”

“I am going to close because I don’t have the traffic,” she said, noting that most of her African-American customers have left the neighborhood. “I’m here every day, and people just walk by, and it’s — nothing.”

Rev. Brown sees a literal sign of gentrification in the banners that hang down Fillmore Street, installed by a local merchant’s association.

“Now they have the superficial, cotton candy sign up there, ‘Feel more in the Fillmore,’ but black people have nothing to feel,” he said. “Public policymakers, they have broken up the cultural enclaves in the African-American community.”

As neighborhoods become less recognizable to longtime residents, it’s not only high rent that encourages people to leave, says Malo Andre Hutson, an associate professor of city and regional planning at the University of California.

“People start to say, ‘Well, my barber shop is now gone’ or ‘The place I used to go eat at is gone,’ and then people start to move,” Hutson said. “People not having the same institutions that they used to go to, the cultural institutions, the faith-based institutions … that has a big impact on people’s social relationships, the overall fabric of the community.”

The landmark designation of Third Baptist Church is part of a trend Malo is seeing across the U.S., as a way for neighborhoods to resist gentrification and preserve their culture and history. But saving buildings isn’t enough, he says.

“The congregation may still be moving away, and then they commute in, and so you need a multi-prong strategy,” he said, including economic opportunities, affordable housing and preserving local institutions and businesses.

Rev. Brown says the landmark status helps cement the church’s role in a neighborhood that has changed drastically. At the signing ceremony, he said, “Because of this designation it will forever be known that Third Baptist was here, was reckoned with and made a difference in the lives of people for the better.”