SAO PAULO — Brazilians dressed in green and yellow took to the streets Sunday night to celebrate the election of far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro, an avowed nationalist and open admirer of the country’s former military dictatorship, who critics believe will turn back the clock on Brazilian democracy.

Carrying 55 percent of the vote, Bolsonaro is now set to become the new president of the largest economy in Latin America and the latest populist leader to rise to power in what seems to be a surge of authoritarian governments around the world from Hungary to the Philippines and beyond.

After he’s inaugurated on January 1, Bolsonaro has promised to allow the commercial exploitation of the Amazon, privatize state-owned companies, ease gun ownership restrictions and change the law so that policemen are not punished for excessive use of force.

Sunday’s runoff election was the climax of an extremely polarized and contentious election cycle, marked by violence, misinformation and attacks on the country’s 33-year-old democratic institutions. Throughout his career, Bolsonaro has not minced words in his adoration of the country’s 1964 to 1985 military dictatorship. During the 2018 presidential campaign, his rhetoric hinted at a desire to return to the strongman form of government that caused so many civil rights abuses in the past.

A former army captain turned congressman, Bolsonaro ran for Partido Social Liberal, a small economically liberal and socially conservative party. They defeated the traditional Workers’ Party, represented by Fernando Haddad, a lawyer who has been both Minister of Education and mayor of São Paulo.

Bolsonaro is seen by many critics as a rising authoritarian, and a real threat to democracy in Brazil. In a 1999 interview, the then congressman said that, if elected president, he would immediately shut down Congress “because it doesn’t work.” In 2016, while voting to impeach former president Dilma Rousseff – who was arrested and tortured in the 1970s – he honored Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, a colonel that ran one of the dictatorship’s main repression centers where opponents of the regime were tortured.

Last weekend, speaking to supporters at a rally, he said he would wipe the “red criminals” – red is the color of the Workers’ Party – out of the country. In a video, his son, congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, said that it would only take two soldiers to close the Supreme Court if it questioned his father’s candidacy – a severe comment in a country that has only re-established its democracy in 1985, after a 21-year military dictatorship.

Bolsonaro incessantly attacks the media and is known for his offensive remarks towards the left, women, LGBTQ and black people. His positions have earned him the support of former White House adviser Steve Bannon, who sees him as an addition to the world’s “global populist tide.”

“Captain Bolsonaro is a Brazilian patriot, and I believe a great leader for his country at this historic moment,” Bannon said in a text sent to Reuters.

The election results show that most Brazilians hope Bolsonaro will bring change to the country.

“We are tired of being robbed,” said 64-year-old hairstylist Sonia Regina Peres, at a rally in São Paulo a week before the runoff. Peres says she has supported the Workers’ Party in the past, but got frustrated with the corruption scandals the party was involved in. Now, the country needs someone different. “We have to put a warrior there that fights for our country.”

How did Brazil get here?

After ruling Brazil for more than a decade – making it the world’s sixth largest economy and lifting millions out of poverty – the center-left Workers’ Party was removed from office in 2016, with the impeachment of the country’s first female president due to an accounting maneuver to cover budget gaps.

Brazil’s political establishment was already shaken, thanks to a sweeping investigation, “Operation Car Wash,” which started in 2014 and uncovered an unprecedented corruption scheme involving the state-owned oil company and dozens of politicians from the country’s main political parties. Many party leaders are now in jail, including former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the most important politician from the Workers’ Party. Lula was the favorite to win the 2018 election until his candidacy was blocked in August. Haddad replaced him on the ballot.

To top it off, Brazil’s once booming economy entered into recession in 2015. It slowly began growing again in 2017, but nearly 13 million Brazilians are still out of jobs.

Frustrated with corrupt politicians and fed up with the Workers’ Party, Brazilians wanted someone new, with no strings attached, who could end corruption and put the country back on track. And along came Jair Bolsonaro, who was framed as outsider – even though he has been a congressman for 27 years – with a clean record.

“All of the money that goes to corruption will now go to those in need: people in the Northeast, entrepreneurs…,” says 39-year-old Ligia Paula who attended a recent pro-Bolsonaro rally. The pet shop owner hopes the “honest” politician “who has God in his heart” will set the conditions for her small business to grow. “Taxes will be lowered, jobs will be created and the economy will take off.”

Sociologist Esther Solano, a professor at the Federal University of São Paulo who researches the rise of the far-right in Brazil, says that the anti-Workers’ Party and the anti-political class sentiment were exacerbated by the economic crisis. This made Brazilians desperate for a change that would quickly solve the country’s complex problems.

Many people believe that “the way out is not through a party or an ideology, but through a hero, a “savior” that is coming to save us all,” Solano said. She adds that Bolsonaro – nicknamed “myth” by his supporters – combines Latin America’s tradition of associating politics with personalities, such as Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez, with the new global wave of right-wing populist leaders, such as President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán of Hungary, National Rally party president Marine Le Pen of France, and increasingly American President Donald Trump.

Attacks on minorities

Solano lists a third factor that contributes to Bolsonaro’s rise: much like his far-right counterparts, he represents traditional conservative values. Throughout his career, Bolsonaro has gathered a long list of offensive remarks, including that a fellow congresswoman was “too ugly to rape” and that he would “beat up” a gay couple if he saw them kissing.

While not all backers agree with these positions, a flurry of funny memes and playful videos with aggressive messages towards minorities took over the internet this election cycle. It’s what Solano calls “pop right.” “It’s is a very harsh hate speech, in a format that is seductive, light and fun,” she explains. The consequence, she says, is that many people are attracted by the rhetoric without recognizing it as hate speech.

Ligia Paula, the pet shop owner, says Bolsonaro’s “jokes” are often taken out of context by the media, which leads to wrong interpretations. “They only show Jair, in a moment of fury, saying what he shouldn’t have.” Paula says she doesn’t trust the “biased media” anymore: “I prefer to believe the true people of the internet than the media.”

Fueled by false information, the “pop right” messages found the perfect online environment to spread in Brazil: WhatsApp. The private messaging app, used by 66 percent of voters, was decisive in this election, according to Yasodara Cordova, a Brazilian senior researcher at the digital Harvard Kennedy School. She explains that free access to WhatsApp and Facebook is included in most cell phone plans in Brazil, while users have to use their data package to visit other websites, such as newspaper portals. “Since people don’t have access to the internet’s full potential, they receive content, but can’t verify it,” Cordova said.

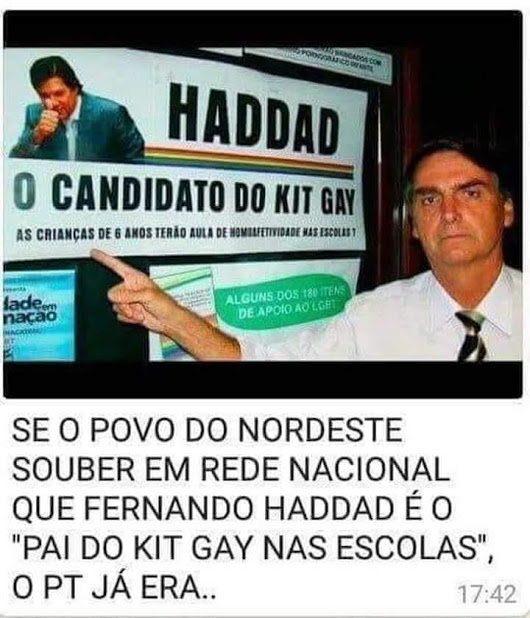

Some lies that were widely spread included that as Minister of Education, Haddad created a “gay kit,” materials for public schools that would teach kids to be gay, and that his vice president candidate, Manuela D’Ávila, wore a T-shirt with the saying “Jesus is a transvestite.”

The dissemination of false information through WhatsApp in this election was characterized as “unprecedented” by Laura Chinchilla, former President of Costa Rica and head of the team of experts sent by the Organization of American States to observe the presidential vote in Brazil.

The extent to which political campaigns used the app to spread false information is still unknown. However, an investigation by newspaper Folha de S. Paulo revealed that companies funded the dissemination of anti-Workers’ Party messages on WhatsApp, which could be considered an undeclared donation to Jair Bolsonaro and an electoral crime.

Authorities are now investigating the case and the retaliation it generated – the journalist who revealed the scheme was threatened and the newspaper was attacked online. This was only one of the 141 cases of threats and violence against journalists registered by the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji) this election cycle. Most cases were carried out by Bolsonaro supporters, according to Abraji

This election will be remembered as the most violent in recent years, according to experts interviewed by Folha de S. Paulo. Bolsonaro himself was nearly killed after an opposer stabbed him at a rally in early September. He was hospitalized for 22 days and has since been campaigning from his home in Rio de Janeiro.

At least 50 cases of politically-motivated violence were documented by the press since the beginning of October, according to the study Victims of Intolerance, made by the investigative journalism organization Agência Pública and Open Knowledge Brazil. Cases include a anti-Bolsonaro female voter in São Paulo who was arbitrarily arrested, assaulted and kept naked in a police station cell, and a black Capoeira leader in Bahia who was murdered by a Bolsonaro voter after declaring his support for the Workers’ Party.

What now?

Opposition against Bolsonaro was intense. In the weeks leading up to the runoff, street demonstrations across the country gathered thousands of women and minorities around the slogan “Not Him.” Artists, activists and much of the country’s political class rallied behind Haddad arguing that, despite political differences, he was the only candidate who truly supported democracy.

For many, it might be a matter of survival. NGOs and grassroots groups are worried about Bolsonaro’s pledge to end activism in Brazil, made on a recent video.

“We don’t know if we’ll be pushed into illegality for fighting for the end of violence against women and for the legalization of abortion,” says Maria Fernanda Marcelino, a militant of the Marcha Mundial das Mulheres (Global Women’s March), a feminist group that has fought for women’s rights for the last 18 years. “It’s all up in the air now.”

The situation is, perhaps, even more pressing for MST, Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (the Movement of Rural Workers with No Land), a 34-year-old grassroots movement that fights for land reform by occupying non-productive lands. One of Bolsonaro’s campaign promises is to classify their actions as “terrorism”.

Rural worker Kelli Mafort is 42 and has been a member of MST for the last two decades. She says MST will keep fighting because they need to. “Our struggle is for land, housing and work, and our home is in the camps and settlements where we fight,” Mafort said. “We are not afraid of him. As long as there are people without land, we’ll keep doing our job.”

Activists fought until the last minute to gather votes for Haddad. One day before the runoff, dozens of people were seen campaigning, distributing flyers and talking to voters on the streets of São Paulo.

One of those initiatives was a parade of dozens of Carnival street groups in downtown São Paulo. Using colorful clothes, with their faces painted with glitter, thousands of protesters danced and sang “not him,” “no step back” and “dictatorship never more” in upbeat samba melodies.

“People may think this is a party, but it’s a demonstration,” said Roberto Mafra, president of Banda do Fuxico, one of the first openly LGBTQ Carnival blocks in São Paulo. Dressed in red with a plastic crown and a sash, Mafra said that he will keep using music and art to fight for his rights as a gay man. “Some people might think that everything will end with this fascism. But it will not. We will only grow stronger everyday from now on.”