It will be hard for history books to encompass the months leading up to the 2020 election. The pandemic surged, killing over 220,000 Americans; fires burned the American West, scorching more land than any year in California’s history; sustained protests against police brutality filled the streets for weeks nationwide. In Portland, Ore., they’ve continued for five months and counting.

At the intersection of these momentous events stand those disproportionately impacted by environmental degradation, barriers to healthcare and intergenerational fear of violence and racism: Black Americans. And in the run up to what has been deemed the most consequential election in American history, all eyes are on the power of the Black electorate.

Black voters have long been a political force in America. After the Voting Rights Act helped secure equal access to the ballot box in 1965, Black Americans have shown up to vote at incrementally higher rates nearly every year. Since 1992, no candidate has secured the Democratic nomination for president without also winning the majority Black vote. This year, the overwhelming support of Black voters may’ve handed Joe Biden the Presidential nomination, and it could also hand him victory.

Sign Up for GroundTruth Weekly

President Donald Trump may have gained an edge with Black voters in 2018 with the passage of the First Step Act. Still, the administration’s attempts to limit access to affordable healthcare and overall failure to directly address issues of white supremacy, among other policies that are particularly important to Black Americans, have added to an overall growing dissatisfaction of the President which analysts expect to fuel record-breaking Black voter turnout in the general election.

“It’s not going to take much to mobilize Black voters. Records will be broken,” said Richard Fording, a political scientist specializing in race at the University of Alabama.

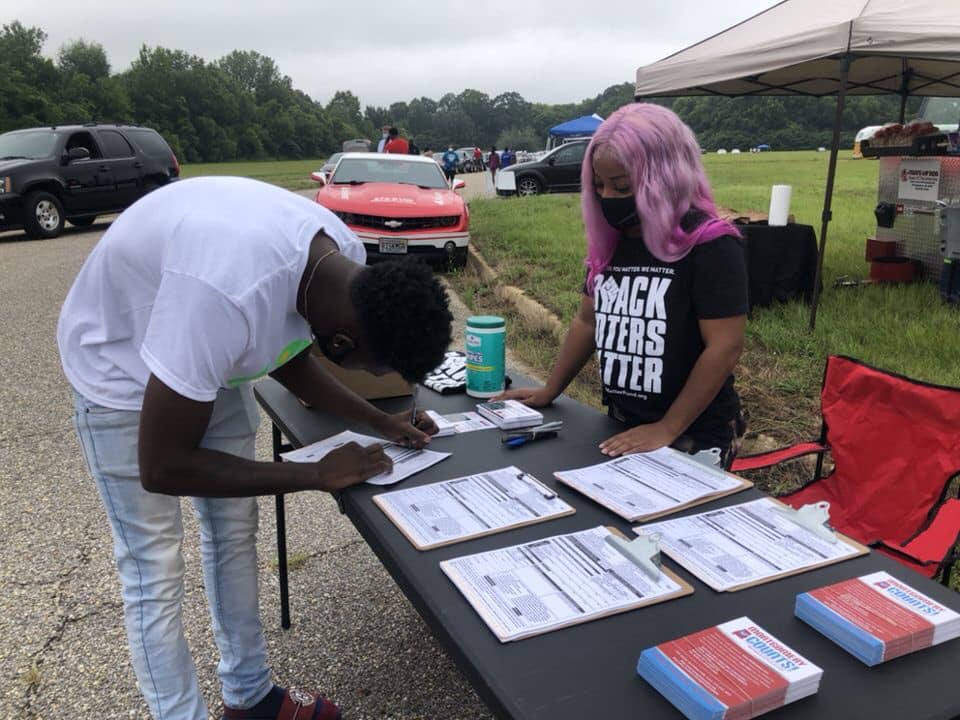

In May, police killed George Floyd in Minneapolis, and a nine-minute video sent shockwaves across an already fraught nation. And the growing momentum behind the Black electorate exploded, a rare intersection of civic unrest, social movement and mobilization to the ballot box that voting rights activists capitalized on to secure an unprecedented turnout.

Related: A spark in Minneapolis: From grief to activism

GroundTruth Voting Rights Fellows and Report For America Corps Members set out to cover the story, of voting rights activism, of voter intimidation and suppression and of the Black electorate carving a path to this polarizing election, one that is sure to define the landscape of American democracy. It is a story of racial reckoning 400 years in the making, especially crucial amid a pandemic that has killed one in 1,000 Black Americans, a rate nearly twice that of white Americans.

We started in Alabama, the birthplace of the civil rights movement and current battleground for voting rights, a state the Southern Poverty Law Center called “one of the most difficult for an eligible voter to register and successfully cast a ballot.” Veteran civil rights icons shared their stories of living through generations of Black voter suppression, in its many iterations.

Related: Alabama’s get-out-the-vote activists fight back against voting restrictions

Distressed by the use of the same tactics of intimidation and disenfranchisement – those that fought tooth and nail to abolish in the ‘60s – they remain humbled by witnessing the next generation carrying on the cause.

“I have a profound appreciation for what the younger activists are doing in the streets today in terms of building awareness and trying to create change in this country,” said Jennifer Lawson, a civil rights activist who at age 13 marched in the 1963 Children’s March of Birmingham, Alabama.

During nationwide protests for racial justice, voter mobilization groups made a concerted effort to register a record number of Black voters. In Iowa, corps member Kassidy Arena spoke with students at the Brown and Black Forum, the oldest minority presidential forum in the U.S., who shared concerns about disinformation and voting rights for former felons. Corps member Sarah Volpenhein covered increased early turnout, after a slight dip in 2016, of Black voters in the contested state of Wisconsin.

Corps member Adria Walker spoke to Professor Frank Kuhn at the University of Mississippi, who unearthed archival photographs from the famed 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer. Seeing vestiges of those images from the ‘60s from the lens of today’s Black activism and white allyship, he set out to revive the documentary-style theatre production “Voices of Freedom Summer,” streaming until Election Day.

And Black women, long established as the Democratic party’s most loyal voting bloc, proved to be the driving force behind this momentous summer and fall. In Baltimore, corps member Tatyana Turner highlighted the work of Nykidra Robinson and Black Girls Vote. In Washington D.C., Aja Beckham noticed a mural depicting suffragists of color, a renewed commemoration of oft-ignored figures on the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. And nationwide, in an effort led by Black Voters Matter, co-founded Latosha Brown, Black women demanded that Joe Biden make history by choosing the first Black, female vice-presidential nominee.

“We were willing to risk it all,” Brown said. “We knew that now is the time.”

These are the stories of Black voters navigating the turbulent, historic months leading up to Nov. 3. They are part of the year’s unprecedented political engagement which, as told by the Civil Rights elders before them, will pave the way for generations of Americans to come.

Megan Botel is a Voting Rights and Preserving Democracy fellow with The GroundTruth Project. Follow her on Twitter: @meg_botel.