Editor’s note: The reality TV show Big Brother may not be as popular in the U.S. as it used to be, but in Brazil it is still an impressive cultural phenomenon. In its 22nd season, the program dominates the trending topics on Twitter, inspires memes, and receives extensive media coverage devoted to every twist in the house. Known as BBB, the Brazilian show is so popular that it recently set a Guinness World Record for the most online votes for a television program, surpassing American Idol, with over 1.5 billion votes for one single episode.

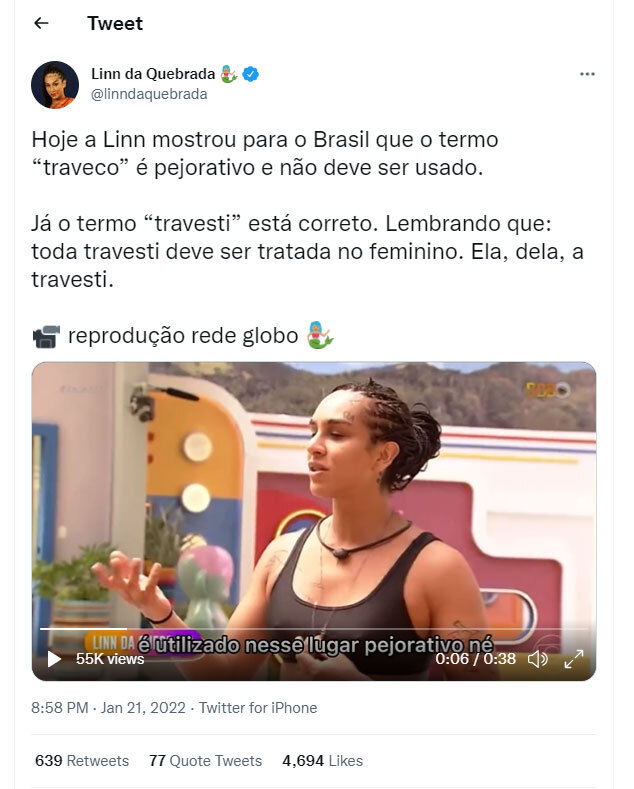

The national obsession with BBB also has become an opportunity for the country to look at itself in the mirror. In this season the presence of Linn da Quebrada, a black trans woman who identifies herself as a transvestite and has tattooed on her forehead the word “she,” has contributed to amplify the national debate over language, body, and gender violence.

While watching Linn and the other participants interacting in the house monitored 24h with cameras and microphones, Brazilians have witnessed how prejudice challenges the everyday lives of all those who defy the traditional gender norms.

Read the original story in Portuguese in Marco Zero:

Lina Pereira, known by her stage name Linn da Quebrada, is the second trans woman to participate in Big Brother Brasil. Unlike Ariadna Arantes, a transgender woman who participated in 2011, Linn was not eliminated in the first week of the show and remains in the dispute for the cash prize of 1.5 million BRL. (around US$300,000)

Her presence has generated debates because of the acts of transphobia by other participants of the house, who claim to have trouble figuring out how to call her and how to behave in front of a transvestite, using the alleged lack of knowledge to justify gender violence.

A cultural agitator, as she likes to introduce herself, Linn has a vast career as an actress, presenter, director, singer, and songwriter. For this reason, in BBB she is part of the celebrities team – despite not being recognized by some housemates. The multi-artist’s participation in the reality show was seen by many as an opportunity to give visibility to transvestites and non-binary people, also contributing to the confrontation of stigmas built in the population’s imagination.

“It is very important to have a figure like Linn da Quebrada, a Black transvestite, being shown on prime-time TV, especially because she promotes important political discussions in her works. The BBB has a huge audience and I believe it is interesting to promote a gender debate and make it possible for many people who previously did not have access to this type of discussion to have access to this type of discussion”, said Jarda Araújo, social worker and executive secretary of Youth in the city hall of Recife. Like Linn, Jarda identifies herself as a transvestite and insists on being addressed by female pronouns.

A sign that Linn is aware of the political and social importance of her participation in the reality show was printed on the shirt she used to enter the house. Her clothing had the image of Anastácia – an enslaved black woman who lived in Brazil in the 19th century and is worshiped as a folk saint – with a smile, and the phrase “Free Anastácia”. Anastácia is usually pictured with a gag in her mouth, and the piece of art in which she appears without it was created by visual artist Yhuri Cruz.

“Neither man nor woman, I am a transvestite”

In her introductory speech at the house, Linn stated, “I am neither male nor female, I am a transvestite.” The speech confused some people and sparked a debate about the difference between identifying as a transgender woman, as participant Ariadna Arantes did, or as a transvestite, like Linn.

According to Dália Celeste, a researcher with the Network of Security Observatories in Pernambuco, the difference between the two terms is established in a political and social way. “When we talk about the term trans, we perceive a process of hygiene because it is much more beautiful to say ‘I am a trans woman’ than to say ‘I am a transvestite’, because the transvestite identity is a historical identity that carries a whole process of marginalization, so when we talk about transvestites, we already refer to prostitution, marginalization, violence. It’s as if the word transsexual came to bring more softness, it’s the same thing as saying ‘I live on a periphery’ or ‘I live in the favela’”, she said. Dália also prefers to be identified as a transvestite and says that the choice is “something totally political”.

Despite having explained from the first day that she identifies herself as a transvestite and having the pronoun “she” tattooed on her forehead, Linn needs to reaffirm all the time that she wants to be referred to by female pronouns and needs to correct the other participants who insist on treating her as a male. Such transphobic attitudes are often justified by a “respect” for the Portuguese language. Not quite, explains Iran Melo, a Ph.D. in linguistics from the University of São Paulo (USP) and director of the Brazilian Observatory for Gender-Inclusive Language: “The issue is less about linguistics and more a political debate of a logical nature about gender, because every time we need to deal with reality and give existence to things, we use language. What happens is that we have a cultural convention, colonial and western, of gender, corporeality, subjectivity and sexuality, which is marked in a male and female binarity”, he states.

“When we don’t know what gender people identify, instead of using forms that will not fit them in the ways that reveal the binarity, we choose masculine forms as generalizing and this is a consequence of living in a masculine society. We make a relationship of correspondence between language and what we have in our culture, but we already have several forms in the language that accounts for the escape from binary. The word ’person’ itself is an example of this,” said the researcher.

Melo also stated that the construction of a less masculinist language began at the end of the 20th century and at the beginning of the 21st century with the work of feminists and has gained even more strength with the claim of non-binary people. “There is a glotopolitics, that is, a policy that promotes constructions in the language. Language constructions for the visibility, representation and inclusion of non-binary people. Unfortunately, this movement still faces a lot of resistance from fundamentalists who claim that this is a threat to our language, but these people forget that language is what we do all the time in interactions,” he concluded.

Transphobia and entertainment

Referring to a transvestite or transsexual person as a “she-male”; calling Linn a “male friend”; texting Linn asking if she’s a “single man”; to demand that Linn be didactic and patiently teach about transphobia. These were the agressions Linn suffered in her first week in the house and that probably affected all the LGBTQIA+ people who follow Big Brother Brazil.

“I am determined, courageous, fearful, complex and contradictory.

I’m not a man or a woman, I’m a transvestite!

Images: TV Globo”

“There are a number of events that have impacted the way Brazilian society looks at transvestites. The astonishment that Linn’s participation causes says much more about the expectations that the public has about the body and posture of a transvestite and about how she has broken those expectations. People are not uncomfortable with Linn, but with the disappointment of seeing all the deconstruction she is promoting, people are living with a calm, intelligent, sensitive person, not a violent person, going against stereotypes”, said Caia Maria Coelho, researcher and vice-coordinator of the New Association of Transvestites and Transsexuals of Pernambuco.

Caia regretted the program’s stance in not publicly calling what happens in the house as transphobia. “On Sunday, Tadeu [host of the program] asked Linn why she had the word “she” tattooed on her forehead and Linn took a stand. It was an important position, but I find it saddening that the word transphobia was not used by the host of the show, because this violence needs to be named and even more, it needs to be treated not only as a crime but also as a media and state policy. “, she said.

The host asked the question after participant Laís Rodrigues sent an anonymous text to Linn asking if she was a “single man”.

“The crime of transphobia (as defined by the country’s Supreme Court) is equated with racism, so when we talk about racism, it is necessary that the harmful act affects an entire group, which is why we almost never see anyone being condemned for racism. That’s why in the case of Laís and Linn we see that transphobia happened, but legally it is not equal, because it is not affecting an entire group. They could equate it with an insult and not treat it as homophobia or transphobia”, explained researcher Dália Celeste.

Searching for belonging

Despite having strong support from the audience, Linn da Quebrada has felt lonely in the show. She feared that her housemates would vote her out in the first week, which didn’t happen. The relief of not having been voted for eviction was short-lived, as the next day, in the dynamic known as the “game of discord”, the houseguests had to choose who they considered would be the three favorites to reach the final of the competition. Linn was not part of any of the podiums, which left her pretty shaken.

“No one voted for Linn to be evicted from the house, but no one put her on the podium either. So then we see the cisgender game, which is to think: ‘I’m not going to vote for her so that Brazil doesn’t think I’m transphobic or transphobic, but I don’t want her in my group either.’ It’s the same thing that we live daily out here: you can occupy that place, but on the other hand, no one will create bonds and establish relationships with you,” Dália analyzed. She, who is also a psychology student, recalled a similar case that occurred to her in her early college years when she was excluded from group work without any justification.

Dália knows what she is talking about when she refers to transphobic violence: in March 2018, she was beaten by two men on the Federal University of Pernambuco campus.

Two other participants, in addition to Linn, were also not placed on the others’ podiums, but they were not as shaken as the artist. Jarda Araújo explains why: “The lack of access, the denial of spaces, the difficulty of being observed and being understood as someone able to be in a certain place, there are several factors that, for us as black people, trans people and transvestites, have a much greater weight and affect our corporeality in a much more intense way. Acts like these make us question whether those spaces are really for us even if we have the capacity to be there and the ability to build a path, in Linn’s case, to the podium”.

This story was produced with support from Report for the World, a The GroundTruth Project initiative.