BLUEFIELD, W.Va. — It’s been two decades since the city of Bluefield settled a lawsuit with Robert “Robbie” Lemont Ellison, a then 20-year-old Black man left paralyzed after an arrest by city police.

In addition to paying $1 million and pledging to diversify the ranks of police officers, the city promised to establish a panel of civilians to review allegations of police misconduct.

Yet, despite the city’s vow to make its police department more accountable, the Bluefield Citizen Review Panel has operated out of the public eye since its founding in 2000. Its four meetings per year, for instance, are closed to the public. It hasn’t produced all of its required annual reports. The minutes and recordings of meetings are exempt from the Freedom of Information Act, meaning the panel’s work avoids public scrutiny by citizens or the press.

Moreover, the police department keeps incomplete records on the race or ethnicity of those the police encounter in traffic stops and arrests, making it impossible to accurately assess the full scope of officers’ interactions with communities of color.

Earlier this summer, after West Virginia Public Broadcasting filed several Freedom of Information requests to obtain previous records of the group’s previous meetings — including recordings — city officials took the extraordinary step to review the panel’s work and procedures.

Last month, city leaders agreed in September to “codify” the panel’s deliberations. What that means, according to City Attorney Colin Cline, is that future meetings will be subject to the state’s Open Governmental Proceedings Act.

“We definitely need to improve the operation and transparency of that entity, that is that is the goal,” Cline said. “I mean, it makes me uncomfortable to have to improve the operation and transparency of a city entity, but, you know, it’s our job.”

The attorney who originally represented Ellison, who later died from medical complications, applauded the move by Bluefield and hopes the panel will accomplish what it was supposed to do two decades ago and be “a more meaningful entity in the future.”

For Ellison’s family, justice remains elusive.

“I don’t know, maybe I’ll be six feet under the ground by the time [things] change,” said Lynn Ellison, Robbie’s older sister. “If it never happens with my brother, maybe down the line for someone else.”

***

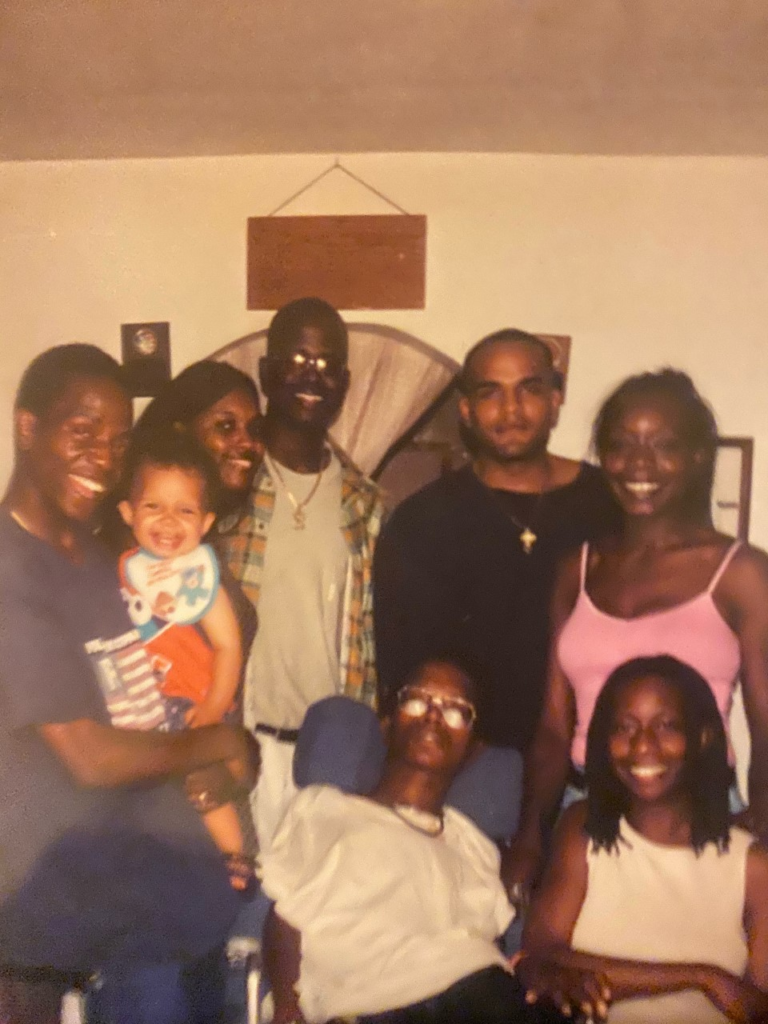

Robbie Ellison was the youngest of eight siblings. Although most of his family has left the area, their roots in southern West Virginia run deep. Robbie’s uncle, John, is a West Virginia Music Hall of Fame inductee who penned the classic “Some Kind of Wonderful.”

The Ellisons still return home almost yearly to see their father, who lives among a row of houses with raised porches across the train tracks that jut through the town.

“This is the place we love, it’s our home,” said Sam Ellison, one of Robbie’s older brothers. “No matter what happened here, no matter what things we had to deal with growing up, this is our home.”

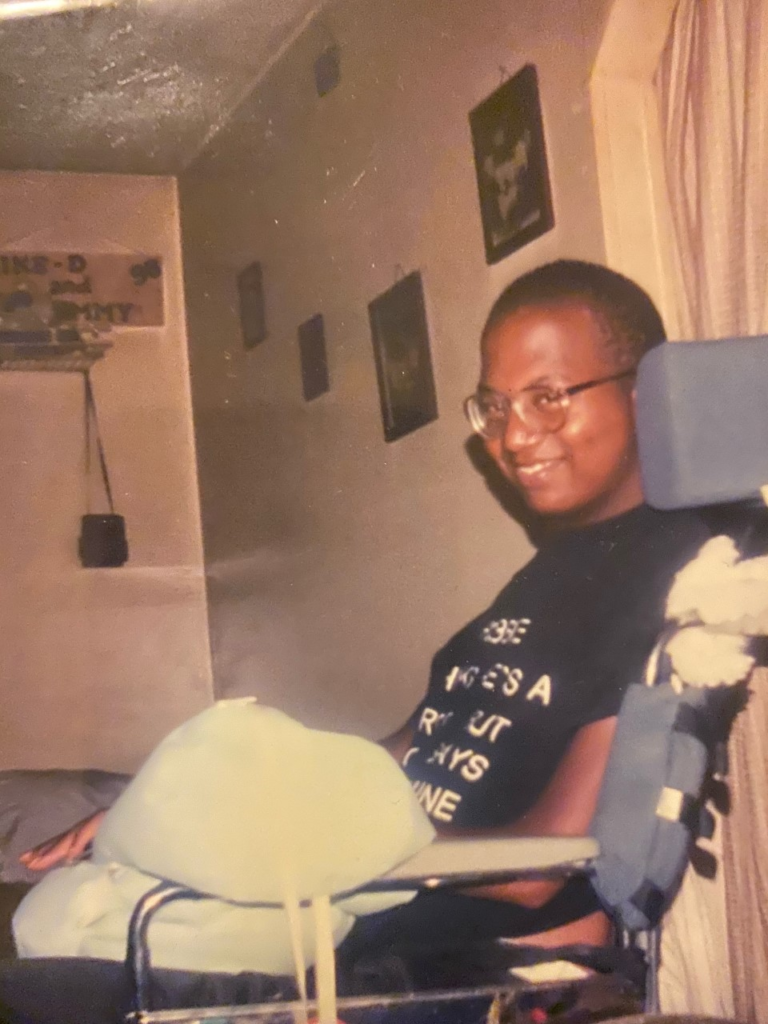

This summer, amid the coronavirus pandemic, they sat in a circle on outdoor furniture and a thick white ledge spanning the width of their father’s home, talking behind cloth face masks about who Robbie was — a lanky kid whose glasses reminded them of Steve Urkel, the character who starred in the 1990’s American sitcom Family Matters.

The Ellisons and Robbie’s attorney contend his 2002 death was the result of the injuries he suffered in 1998. The three police officers involved in the arrest, two of whom Ellison said beat him, were not criminally charged in the case.

“As a police officer, you have to protect yourself, but I think that what they did was they went to the extreme with the force that they used on my brother. I know they did, because they paralyzed my brother,” said Sam Ellison.

Nearly 20 years later, Robbie’s uncle John released a song that he first wrote in 2003, a year after Robbie’s death, about the injustice his family and Black Americans have seen — “Wake Up Call (Black Like Me).”

“The bottom line is, his neck was broken, his head was bashed and, you know, from what I saw in pictures of what it was done to him, it was very cruel,” John said. “If this police officer’s life was being threatened, that’s a totally different scenario. But one thing is for sure, he wasn’t armed, he posed no threat to this officer. And they basically broke his neck. They killed him.”

***

Police Chief Dennis Dillow — one of the three officers named in Robbie’s original lawsuit — attributed the injuries to Robbie’s actions.

Robbie Ellison was resisting arrest, Dillow said, and while he was struggling he took what Dillow called a “diver’s accident.”

“When he went to the ground, he had what was called a diver’s accident,” Dillow said in an interview in July. “Where he hit his head, you know, on his forehead. He landed on his forehead, and it caused the compression in his neck that severed his spinal cord.”

In the lawsuit, Robbie’s attorneys said the officers slammed their client against the back of a car so hard that blood was present the following day. Attorneys also referred to witnesses who said they saw the officers hit Robbie, even after he was in handcuffs.

Officers countered that they were cleared of wrongdoing by an internal investigation and by an FBI investigation in the late 1990s.

As chief for the last eight years, Dillow says he’s brought accountability to the force and tackled some of the “good ol’ boy” nature that police departments are sometimes accused of — the same “blue line” and “code of silence” attorneys for Robbie accused police officers of during his lawsuit more than 20 years ago.

In 2015, under Dillow’s administration, the city signed its first contract for police body cameras.

“I wish we would have had body cameras for that, because then things wouldn’t have been portrayed the way that they were,” Dillow said.

Under Dillow’s own policy, which was revised four years ago, there’s clear penalties for not wearing a camera or turning it off.

“I just think that it’s a necessary tool that should be on every officer’s chest, as much as the badge that he wears,” Dillow said. “Because it just, it saves you from frivolous complaints, all the way up to some major event.”

***

Ed Hill, one of three attorneys who represented Robbie in his original complaint against the city, said the city’s Citizen Review Panel created after the lawsuit was settled has been riddled with “pitiful non-compliance” for more than 20 years. He said the city’s decision to create a new panel is a good first step.

“I think by codifying this, making it more transparent, perhaps getting new members on the panel, I look forward to this being a more meaningful entity in the future.”

According to the new city ordinance, drafted by city attorney Cline with input from Hill, the five-member board will continue to meet quarterly and they’ll be required to submit annual reports on their work to city leaders. Cline — who joined the city three years ago and wasn’t until recently familiar with the panel’s origins — will attend all quarterly meetings.

Because the group hasn’t met publicly for the last 20 years, its minutes have been exempt from FOIA law, according to the city’s interpretation of the judge’s consent decree. And, because its meetings have been closed to the public, it’s impossible for the public to judge how effective the group has been.

Get the Latest Dispatches from across America

Sign up for our weekly On the Ground roundup

The newly revamped panel still faces obstacles in carrying out any full assessment of the police department.

That’s because while the police department relays racial and ethnic information to the FBI for violent and property crimes, there’s no data on traffic stops, citations and other types of arrests, which the FBI doesn’t collect.

What little FBI data is available shows that police disproportionately arrest Black people in Bluefield, who comprise 26% of the city’s population. Roughly 38% of those arrested for alleged violent crime and 25% of alleged property crime suspects in 2019 were Black.

Meanwhile, 42% of the city’s property crime victims were Black, and at least 28% of its violent crime victims were Black. The city has cleared less than half of its reported violent crimes since 2019 and less than a third of its property crimes.

When West Virginia Public Broadcasting requested records for traffic stops and arrests in Bluefield and their racial breakdown, the city could not provide the data. The reason? The city didn’t keep such information.

***

Criminal justice reform supporters in some of West Virginia’s bigger cities say their efforts to push for more civilian review panels have been unsuccessful. Only two are known to be in operation in the state.

“Police cannot police themselves. That’s just the reality,” said Owens Brown, president of the West Virginia NAACP and a resident of Wheeling, where for three years Brown has been requesting a citizens police review board.

According to Brown, officers are afforded so much authority — including “the authority to stop you, they have the authority to arrest you, they have the authority to incarcerate you” — that there’s a need for more independent oversight.

“It seems as though there would be such stringent checks and balances on these individuals, but there’s not,” Brown said. “And that’s what’s so insane about this situation.”

Emily Allen covers West Virginia state government and the southern part of the state for West Virginia Public Broadcasting. She is based in Charleston, W. Va. This dispatch is part of a series called “On the Ground” with Report for America, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project. Follow her on Twitter: @emilythejourno.